“I don’t mean to sound arrogant, but we had the goods. We knew what we were doing”: how Bad Company conquered in America in the ’70s

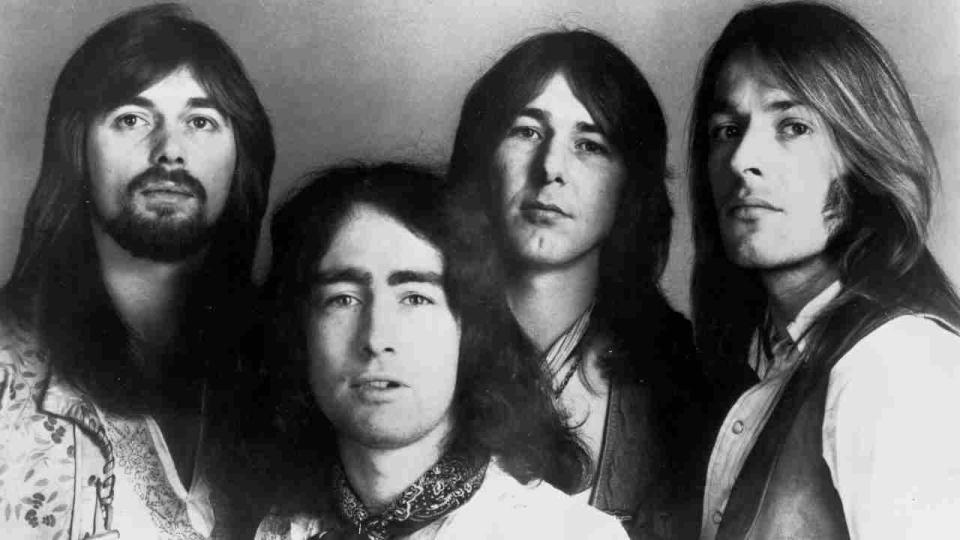

Boston, Massachusetts, October 10, 1974. It was the final night of Bad Company’s inaugural American tour and despite an uninterrupted string of unqualified successes, the exultant mood among the musicians had chilled with the news that their manager, the Herculean Peter Grant, wanted to see them, pronto. Among the four musicians – vocalist Paul Rodgers, guitarist Mick Ralphs, bassist Boz Burrell and drummer Simon Kirke – none could fathom what transgression they might have committed to find themselves called onto the carpet of arguably the most menacing figure in the music industry.

Their concerns were well founded. Grant, a notoriously hot-headed former wrestler, had been known to administer savage beatings to promoters, bootleggers and anyone else who might threaten his interests. As the hottest band in the United States, Bad Company ranked among the highest of Peter Grant’s interests.

Grant had famously amassed his musical empire through his ruthless stewardship of his ‘other’ band, Led Zeppelin, with whom he had launched the Swan Song record label in 1974. Bad Company were Swan Song’s first signing and their eponymously titled debut, recorded in nine blustery days, was the label’s first North American release. Not surprisingly, observers heaped suffocatingly high expectations on this new band and their platinum pedigree, although the men of Bad Company would easily sidestep such concerns, all four being battle-hardened veterans from well-established bands such as Free, Mott The Hoople and King Crimson. Yet where each feeder band had enjoyed a certain level of success, none had come close to conquering the Promised Land of the US.

Free had made a splash with All Right Now, but their distillation of British R&B fell short of commanding North American attentions with a truly classic album. Mott The Hoople were even more inscrutable, due in no small part to a name that would only confound American DJs and record buyers. It smacked of stuffy British pretence, and while Mott’s All The Young Dudes did achieve bona fide hit status, such acclaim was down to the David Bowie connection, rather than their previous studio albums, none of which had gained traction in the US. Likewise, while achieving name recognition and a healthy following abroad, King Crimson’s proggy experimentalism had failed to gain purchase in the colonies beyond the obsessive attentions of America’s record-store junkies and import enthusiasts.

Together, however, the four musicians congealed into a hard-hitting pack of blue-collar rock’n’roll heroes whose steadfast rejection of flash and posing would only endear them to a Yankee fanbase eager for a new sound. In the early days of Bad Company’s release, fans might not have recognised the names of the musicians, but in short order the entire country was buzzing over the first single, Can’t Get Enough. Any lingering vestiges of anonymity would soon evaporate and within two months of that single’s release, they were superstars.

While the response to Bad Company was massive on both continents, there was an immediate and uniquely charged chemistry between rock-thirsty American audiences and this swaggering new supergroup from England. Although Bad Company’s lineage was British to the core, they had a stormy outlaw menace that was all American. That included their name, which they culled from the 1972 Jeff Bridges movie Bad Company, about a spirited Civil War draft dodger and his rambunctious gang of outcasts. Set against the violent protests of the Vietnam war and the explosive revelations of President Richard Nixon’s Watergate scandal, the film would tap into those duelling forces of protest and idealism that fuelled young American audiences in the early 70s.

Moreover, on a romantic level, America has always loved its outlaws. Names such as ‘Mott The Hoople’, ‘King Crimson’ or even ‘Free’ offered precious little insight into the band’s beating heart, but ‘Bad Company’ was something that American fans could get behind.

On the heels of the debut, a supporting mini-tour consisting of a handful of UK dates would showcase the band’s ferocious live presence, setting the scene for their historic 1974 US campaign, beginning one month after the album’s release. Never one for subtlety or nuance, Grant orchestrated their North American advance publicity as a no-holds-barred media blitzkrieg. Danny Goldberg, then Swan Song’s US representative, proclaimed that, “Our entire team is going to be fully concentrated on Bad Company.”

choing Goldberg’s commitment, Pete Senoff, the head of promotions at the time for Atlantic Records, launched an extensive national campaign that included papering the United States with literally thousands of vibrant promotional posters and outrageously over-the-top billboards that cheekily asked, “Does Your Mama Know You’ve Been Keeping Bad Company?”

The higher the band’s stature became, so too did the demand for their time from the American media. Always protective of his boys, Grant aggressively shielded them from overexposure, carefully measuring out their interviews to a hand?picked few outlets, causing one journalist at the time to grouse, “Bad Company will possibly follow Led Zeppelin down the trail to where permission to speak is like a Nobel Prize for Credentials.” This was, of course, precisely the mystique that Grant had been hoping to create.

As reviews of Bad Company poured in, the American press united in both their lofty critical assessments, as well as their prediction that the band stood at the beginning of a meteoric career. Rolling Stone, which had historically held Led Zeppelin in astonishingly low regard (the magazine once referred to Jimmy Page as “a writer of weak, unimaginative songs”), proclaimed Bad Company to be “an uncompromising album, reflecting the wills as much as the talents of the participants, and it’s all the more impressive in light of the fact that it was recorded immediately after the group’s formation… Bad Company could become a tremendous band.”

Meanwhile, Circus magazine hailed the release as “a raw, keen-edged record bubbling with Rodgers’ tenderly tortured vocals”, rightly predicting that the album would launch the band into the strata of superstardom. Creem referred to Bad Company as “the great white hope of the Seventies”, likening the band to the blockbuster movie The Towering Inferno, which also boasted a richly talented, star-studded cast.

American fans hadn’t been waiting for the blessing of their critics to embrace Bad Company as the standard-bearers of the new generation of rock – they were all-in from the iconic one-two beat that kicked off Can’t Get Enough. Behind that anthem and follow-up hits like Rock Steady, Ready For Love and, of course, Bad Company, the album had stormed onto the US charts, muscling upward through the Top 40 to join a company of monster releases, such as Bob Dylan’s Planet Waves, Eric Clapton’s 461 Ocean Boulevard, and Band On The Run by Paul McCartney And Wings.

Meanwhile, the band landed in the US for a six-week coast-to-coast arena tour, starting in mid-July. While the musicians had individually toured the States with their previous bands, the 1974 tour crackled with a new electricity unlike anything the boys had experienced in their previous lives, causing Ralphs to note, “This is just like your first group – everything you do excites you.”

With renewed fervour and bolstered by an album that seemed incapable of stalling, the band criss-crossed the continent, enjoying the exquisite pleasures of rock’n’roll excess in a manner befitting of their label. Rodgers would later recall, “I think the first rush of success really sort of went to our heads and we were a bit over the top, wrecking bars and whatever,” although quickly clarifying, “The music’s the most important thing, not necessarily the image, and there’s no need to try and over-exaggerate the whole badder-than-thou attitude.”

From one city to the next, Bad Company discovered that they held universal appeal, rooted as much in their steadfast opposition to chasing fads as to their simple and emotive approach to songwriting. More than any other time since the rise of Elvis, US audiences looked to music for a release from the seething tensions and gathering paranoia that had overtaken a country beset by war, betrayal and spiralling waves of domestic violence. With a punishing blues-based attack, coupled with unaffected lyrics, Bad Company offered the anthemic majesty and lyrical honesty America craved.

Speaking about this relationship with US fans, Rodgers remarked, “I don’t like lyrics to be overbearing – I like them to say something. But I’m not trying to change the world overnight. Something simple and understandable that people can relate their own everyday experiences to.”

With such towering success would come the spoils of victory which, in Rodgers’ case, played out as a chance to see Elvis Presley performing live. Rodgers chuckled as he later recalled his failed attempt at actually meeting Elvis after the show – a bid brought to a rather unceremonious conclusion when a security guard nabbed him trying to sneak backstage at the tail end of Led Zeppelin’s entourage.

Protesting that he was “with Led Zeppelin”, his entreaty was still denied and Rodgers returned to the hotel, nonetheless happy to have seen his hero performing up close and personal. He would later use his souvenir programme to pull a bit of a prank on his bandmates, assuring them that he had, in fact, spoken with Elvis, offering the booklet as proof. His mates were thoroughly impressed, if not somewhat baffled by Rodgers’ immensely good fortune.

Behind one of the strongest debut albums in history, and with six weeks of hard touring under their belts, nothing could stand between Bad Company and their destiny. On September 28, 1974, Bad Company settled into the top slot on the Billboard Albums chart. They now owned the No.1 album in the United States of America.

History would later reveal Bad Company to be only the second British band to hit No.1 on the US charts with their debut album – the first being The Beatles. “I must say it felt very natural,” Rodgers would later tell Classic Rock. “I don’t mean to sound arrogant, but it felt like we had the goods. And Peter was very clever – put us straight into arenas, often headlining. We’d already paid our dues in Free and Mott and [King] Crimson, so we knew what we were doing.”

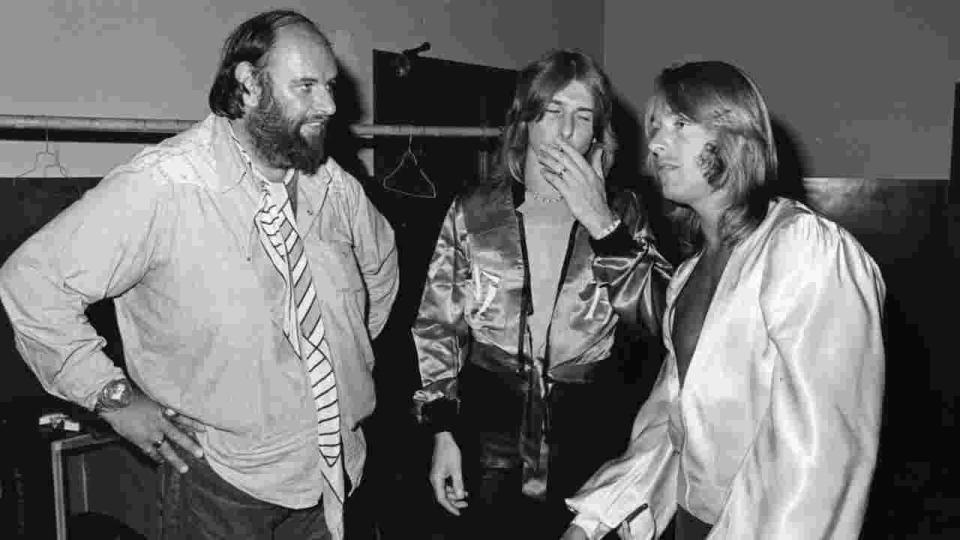

And so, on an unseasonably warm autumn evening in the blue-collar town known as the ‘Cradle of Liberty’, barely a week after reaching the top, the band’s enthusiasm had suddenly withered at the shape of Peter Grant darkening their dressing room doorway, just as they were preparing to take the stage. Simon Kirke recalls: “It was the final night of the first US tour, in Boston. G came into the dressing room; we were just ready to dash out and play. He puts this meaty arm across the door and says, ‘You’re not going anywhere.’ I thought, ‘Oh, fuck me, is he gonna shoot us?’ ‘Let them wait!’ he said. That was one of his stock phrases: ‘Let them wait.’”

Motioning brusquely for them to follow, he led them into an adjoining room. “There was a big sheet on one of the tables and he pulled it back and there were four gold albums. He had tears in his eyes – we all had tears in our eyes – and he gave a lovely little speech and then he said, ‘Now get the fuck out of here and knock ’em dead!’ We shot out of that dressing room like greyhounds chasing the rabbit, and we just put on a blinding show. And that was how Peter did things.”

The fires continued to burn hot when Bad Company returned to the States for a handful of dates in 1975 in support of their sophomore outing, Straight Shooter. That album, like its predecessor, wasted little time making its way into the US Top 10, earning the band a second gold certification a mere month after its release. Not surprisingly, it would be the bittersweet saga of a rock’n’roll cowboy, Shooting Star, that would grab hold of American audiences.

Ironically, that song was also the only non-love song on the album, which also boasted the chart-smashing pair of Feel Like Makin’ Love and Good Lovin’ Gone Bad, songs which, nearly 40 years later, still enjoy regular rotation on America’s classic rock stations. Straight Shooter would fulfil Bad Company’s covenant with their fans by delivering another clutch of soulful and impeccably balanced anthems that met their audience on the most intimate of grounds. As one US reviewer noted, “It’s easy to form an emotional affinity with Bad Company because their lives become intertwined with the lives of the listeners.”

As a gauge of the band’s enduring Stateside success, the Straight Shooter tour would find Bad Company selling out the same venues visited by the likes of Zeppelin, The Who and the Stones. While some have estimated that it typically takes a talented, well-managed band up to seven tours to build a fanbase sizable enough to fill a Madison Square Garden, Bad Company were there on their second go-round. For a point of comparison, consider that Queen, on their third US tour, were playing 3,000-seat venues, while Bad Company’s second campaign saw the band selling out 20,000-seat arenas in the blink of an eye.

If pressed to identify a single event that would put the stamp on Bad Company’s US coronation, it would unquestionably be the evening of May 16, 1976, when the band were preparing to headline a show at the Los Angeles Forum, with Kansas in support. As Bad Company undertook pre?show preparations for their final concert of that tour, across the sprawling, sun-splashed boulevards of Los Angeles, an armada of 12 limousines was departing Beverly Hills en route to the Forum, with a police escort leading the way.

As the motorcade arrived at the venue, from the sunroof of a gold Lincoln, none other than Zep frontman Robert Plant poked out his golden mane to wave to the gobsmacked fans lined up outside. Seeing the adoration and excitement marshalled for Bad Company would only whet his own appetite for performing, and after pulling himself back into the limousine, he would confess to a journalist, “I wish Bad Company all the luck in the world, but… I’m fucking jealous tonight. Really fucking jealous!”

Though ostensibly there to support his Swan Song labelmates, Plant’s enthusiasm through the Bad Company show would not dim. After an impromptu backstage chat following Bad Company, the intended finale, the crowd were rewarded with a bonus encore, with the band joined by Plant and Jimmy Page for a four-song jam that included Train Kept A-Rollin’, You Shook Me, Bring It On Home and I Just Wanna Make Love To You.

The roar of the audience nearly drowned out the levels of the PA system, yet this historic session would only confirm what the 20,000 fans in attendance had known for three years now – Bad Company had joined the ranks of rock’n’roll’s living legends. And on this balmy spring evening, it was official – they had conquered America.

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Bad Company