How Dominick Dunne Invented the Way We Read About the Rich

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

“I had been brought up on stories told by people who loved to tell stories,” Griffin Dunne writes in his spirited new memoir, The Friday Afternoon Club. The storytellers in his family included his uncle, the journalist John Gregory Dunne, and his aunt, who needs no further introduction: Joan Didion.

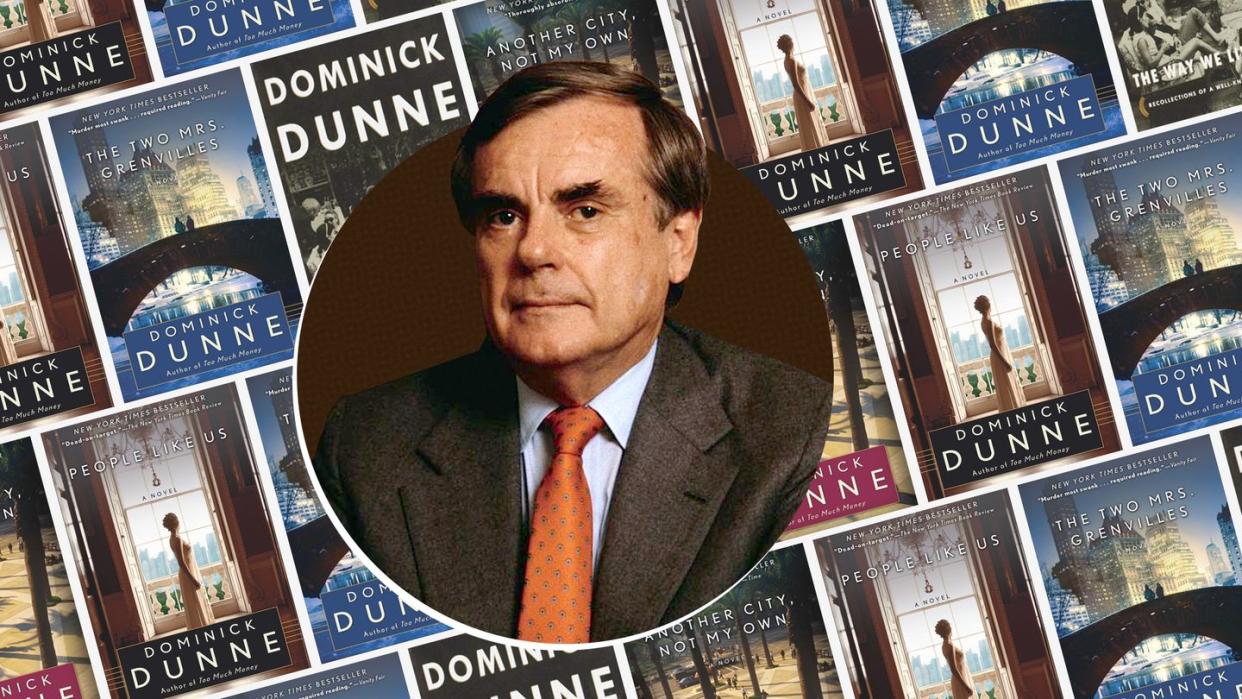

But no one in his illustrious family told a story like Griffin’s father, the producer and writer Dominick Dunne, a man about town and a born raconteur who found a post-Hollywood second act in crime reporting for Vanity Fair and writing bestselling page turners like The Two Mrs. Grenvilles and An Inconvenient Woman.

Griffin’s memoir is full of rich anecdotes about his family life as well as exquisitely detailed stories about parties and celebrity encounters that could be right out of his father’s novels.

The typical Dominick Dunne novel consists of a swirl of names and faces that readers encounter at various elaborate social engagements: endless cocktail gatherings and formal dinners, fancy restaurant lunches, opera openings, and galas.

If at first such flitting from scene to scene could overwhelm a reader, Dunne brings us into their world so expertly that all of these characters begin to feel, by the end, as familiar as old friends—or more aptly, frenemies. We know all of their trivial concerns, their kinks and foibles, as well as their greatest hypocrisies and the secrets they hold closest.

In his list of Favorite Books For Social Climbers on Goodreads, Crazy Rich Asians author Kevin Kwan cites Dunne’s 1988 novel People Like Us as required reading for those curious about the ins and outs of New York society. “It's devastating, hilarious, razor-sharp social satire at its best, and the circus of characters who populate this novel are thinly veiled caricatures of Manhattan's ruling class."

The Two Mrs. Grenvilles

The Two Mrs. Grenvilles

amazon.com

People Like Us

People Like Us

amazon.com

Another City, Not My Own

Another City, Not My Own

amazon.com

The Way We Lived Then

The Way We Lived Then

amazon.com

But there’s a darker element to Dominick Dunne’s novels beyond the simple chronicling of the rich and richer: each book details crimes that take place in the realm of the upper classes, violence that goes way beyond white collar offenses. Dominique Dunne, daughter of Dominick and sister of Griffin, was a 22 year-old actress when she was strangled to death by an ex-boyfriend in 1982. The tragedy of his daughter’s murder, the tremendous grief of it as well as the ensuing degradation of trying to find justice in the American legal system, reverberates through Dunne’s novels, as well as his son’s memoir. (It's no surprise that the true-crime TV series Dunne hosted was called Power, Privilege, and Justice.)

People Like Us is Dunne’s most autobiographical novel, featuring a protagonist named Gus Bailey, a former Hollywood exec turned journalist who mingles with the well-to-do in the aftermath of his daughter’s murder. When Gus’s ex-wife calls him out for his endless fascination with rich people, he has a simple explanation: “It keeps my mind occupied. It keeps me from going nuts. It keeps me from dwelling on things I can’t do anything about.”

If getting lost in other people’s stories is a timeless coping mechanism, then Dunne is a master of bringing readers into the most private corners and most pressing concerns of the extremely wealthy. Long before Succession and The White Lotus became obsessions for a certain set of voyeuristic TV-watchers, Dunne had tapped into the allure of seeing the ultra rich at their very worst.

Dunne covered his daughter’s murder trial for Vanity Fair in the 1980s, becoming a popular columnist who was on hand for all of the big trials of the age: OJ Simpson, the Menendez Brothers, and Claus von Bülow. His reporting was compelling partially because, as Graydon Carter said in Dunne’s New York Times obituary, “He never pretended to be objective in covering trials, he was always writing from the point of view of the victim because of what happened to his daughter.”

If Dominique Dunne’s murder altered the lives of the Dunne family forever, then it’s a relief to read her father’s fiction, where he has the freedom to invent at will even if his subjects are very much ripped from the headlines. His thinly veiled portraits of actual true crimes involving the elite—the Bloomingdale family (An Inconvenient Woman), various Kennedys (A Season in Purgatory)—are intricately plotted and entirely pleasurable, fictionalized just enough to be titillating while nodding to bold type names. Facts are beside the point when, as Dominick Dunne’s sister-in-law said, we tell ourselves stories in order to live.

You Might Also Like