Death Wish at 50: a reactionary and repugnant revenge thriller

We denizens of the present like to presume a higher degree of moral clarity over the past, but some things don’t require the benefit of hindsight to be correctly assessed. They had Michael Winner’s 1974 film Death Wish dead to rights the first time around, for instance, when a solid faction of critics cried foul at its shameless stoking of reactionary fears about inner-city living.

Related: Chinatown at 50: has there been a greater screenplay since?

In one of his two broadsides against the low-budget thriller turned surprise blockbuster, the New York Times’ Vincent Canby branded it “a tackily made melodrama, but it so cannily orchestrates the audience’s responses that it can appeal to law‐and‐order fanatics, sadists, muggers, club women, fathers, older sisters, masochists, policemen, politicians, and, it seems, a number of film critics”. Some took its despairing depiction of New York City as a lawless hellscape teeming with street criminals at face value; others charged Winner with panic-mongering, playing on a paranoid conservative imagination to his own benefit. So the culture war lines were drawn, and so they remain.

If anything, revisiting Death Wish after 50 years only affirms how little ground has been gained since then. Last year’s horrifying episode in which a former US marine strangled Jordan Neely in response to his erratic behavior on the F train reintroduced the question of extrajudicial killing as a debate with two sides, one faction of partisans rushing to the defense of a citizen they saw as acting in self-defense. (The trial deciding the charges of second-degree manslaughter and criminally negligent homicide has been scheduled for October.) The extreme callousness required to believe that a death penalty without trial is an appropriate response to mugging hasn’t gone away, instead ossifying into a party line. Few have gone so far as to lay out the evident reasoning that if someone’s looking at you funny, they could murder you, and if someone could murder you, you have no choice but to strike first. The right’s vilification of New York, however, has only grown more constant and impassioned.

Venturing from the noble heartland to survey the modern-day Sodom of New York has become an entire genre of social-media performance for GOP ladder-climbers, though their inventories of horrors generally top out at hotdog water (fair), fruit vendors minding their own business, and the occasional person asleep on the sidewalk. There’s a chicken-and-the-egg quandary in determining the degree to which Death Wish inspired fearful fervor versus channeling currents that already existed; crime rates had indeed risen, but things didn’t get really bad until 1975, when the film proved a useful rhetorical cudgel for laid-off police officers distributing the notorious “Fear City” pamphlets in airports to scare away tourists. In either case, Winner’s fantasy of endangerment and empowerment is free to indulge its kneejerk alarm without intrusions from real life.

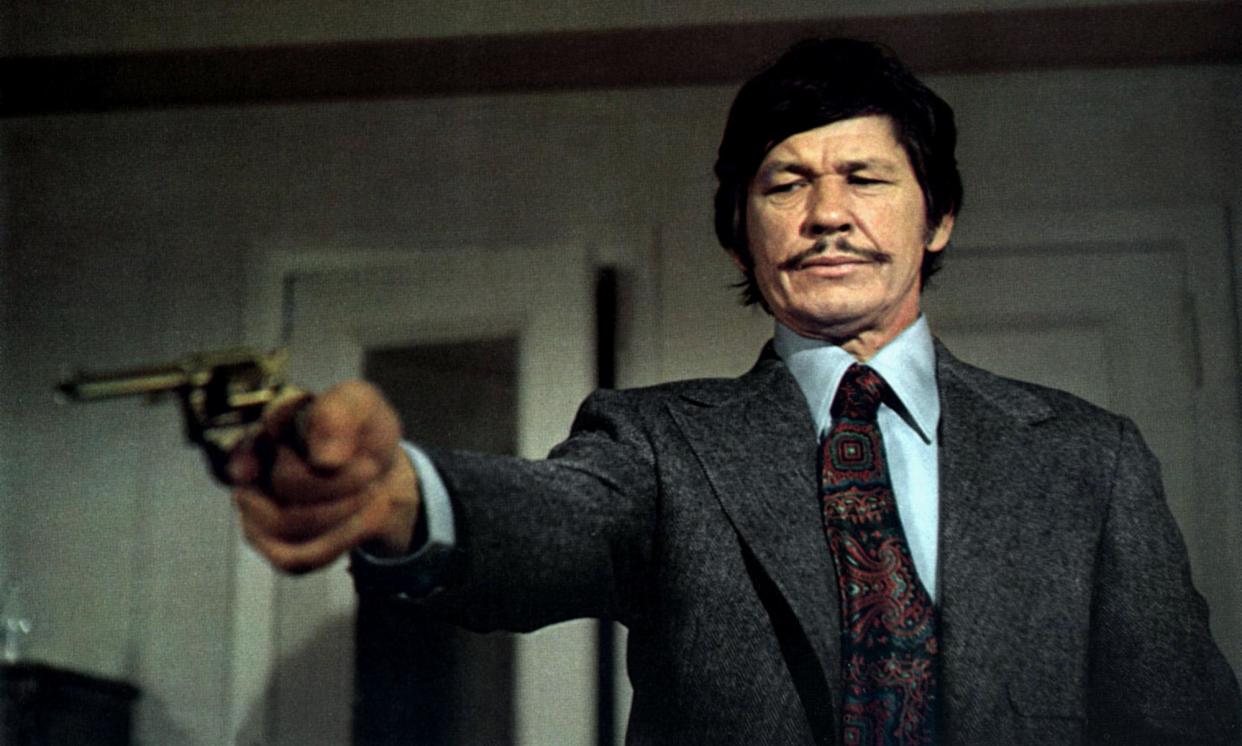

As propaganda goes, Death Wish is pretty shoddily slapped together, all ideological seams and narratively stacked decks. We join the stiff, inexpressive Charles Bronson as architect Paul Kersey while he frolics on a Hawaiian beach with his wife in a scene added just for this adaptation, not nearly the biggest departure from a book that unambiguously condemned the vigilantism Winner and screenwriter Wendell Mayes condoned. The quiet, spacious natural expanses of Hawaii, and later, the Tucson desert – where our man gets an eye-opening lesson in frontier justice and American mythmaking from some wild west roleplayers – both offer counterpoints to the claustrophobic, smog-choked streets of Manhattan. But New Yorkers, we’re shown, aren’t even safe in their own homes; it’s there that a gang of street toughs (led by a pre-fame Jeff Goldblum, in a role that didn’t stop him from attaining heatthrob status) burst in and assault Paul’s wife and daughter in a takeoff on A Clockwork Orange’s infamous rape scene without the artistry or complex intention. The tragedy quickly transforms Paul from a mild-mannered “bleeding-heart liberal”, a perspective the film has no real interest in exploring, into a gun-toting dispenser of vengeance.

Any pretense of nobility goes out the broken window as Paul starts looking for trouble, taking night-time constitutionals to attract hoodlums he can then fatally shoot once they’ve brandished a weapon, no matter if it’s to the back as they run for their lives. (These gangs are also curiously diverse, in a clear measure of plausible deniability for the still-palpable racism left as a glaring structuring absence.) While Winner presents this activation as the stirring account of an antihero with nothing to lose who decided he wouldn’t take it any more, viewers unaligned with its sociological theories may see a dark psycho-thriller about a man processing his grief and guilt by becoming a self-rationalizing serial killer. Or perhaps something even more pedestrian than that: as Paul’s pivot to punishment gives him a new lease on life, compelling him to restyle his now-vacant family home as a swank bachelor pad, the premise comes into focus as a nasty form of escapism for henpecked dads feeling estranged from their masculinity.

Paul’s stand inspires his fellow New Yorkers to stand up to their sidewalk bullies, who are duly cowed by any firm act of resistance. The copycats imply that Paul is acting on impulses everyone shares, channeling a culture-wide spirit of frustration in a way markedly similar to the riot-sparking Joker of Todd Phillips’ 2019 film – another guy who snapped after being pushed too far. At least the Clown Prince of Crime was honest about the simple indulgence of his violent whims, where Paul sees himself as some fashion of civil engineer keeping urban America from going off the rails. Anyone actually schooled in the discipline will tell you the most effective method of lowering street crime has more to do with outreach and pre-empting the circumstances that leave the economically precarious with no other options. But it was never really about improving the material circumstances of the American people for Paul or his innumerable followers, insofar as a society ruled by terror would be hardly worth living in at all.

Paul doesn’t realize that the cowboys putting on a show of rounding up the varmints represent a way of life we were right to evolve beyond, a brutish state of nature that had to give way for civilization to follow. He’s too excited by his place in this world order, by the power and authority he can wield simply by choosing to seize it. This selective self-image of judge, jury and executioner recasts Paul as tyrant, an arbiter with zero accountability and a clear yen for inflicting harm. His fundamental villainy becomes crystal-clear in the final shot, which finds him taking his talents to Chicago and pantomiming a finger-gun at a ne’er-do-well he spots in the airport. The moment plays like the threat it is, or like the final title card of a horror movie that asks “THE END…?” in drippy-blood font. The most disturbing element of the film is now our awareness that that end never came.