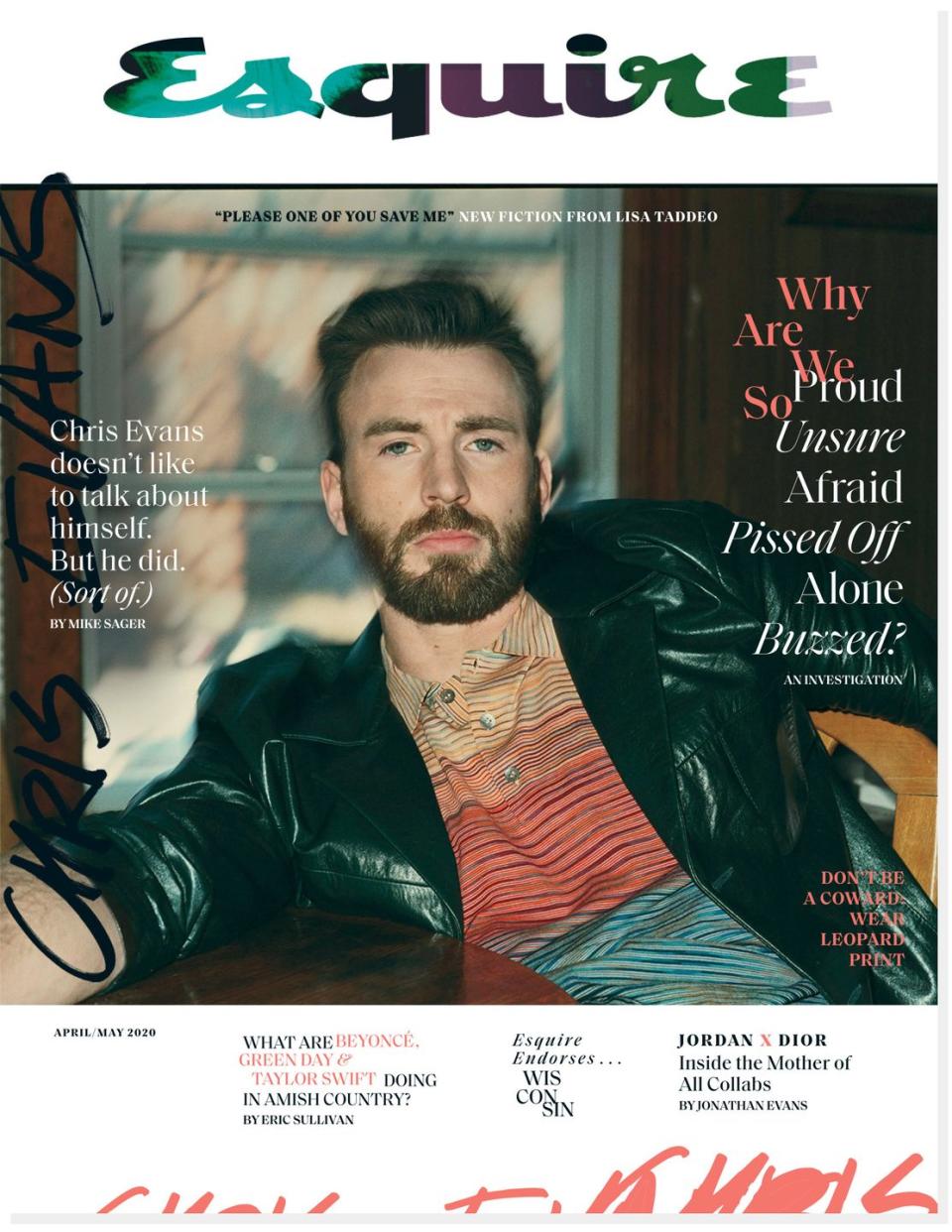

Chris Evans Doesn’t Like to Talk About Himself. But He Did. Sort Of.

The artist formerly known as Captain America is found in seclusion at his rambling farmhouse, set back from the road on a couple of sylvan acres in the Boston suburbs, not far from his childhood home. It’s a warm, late-winter afternoon. The trees are bare. The sky is clear. Patches of melting snow cover the ground.

With his fortieth birthday on the horizon, Chris Evans seems to have undertaken a retreat, returning to familiar ground to regroup. The Marvel Cinematic Universe now behind him, the actor has the time, money, and wherewithal to pursue anything he wants.

All he has to do is figure out what.

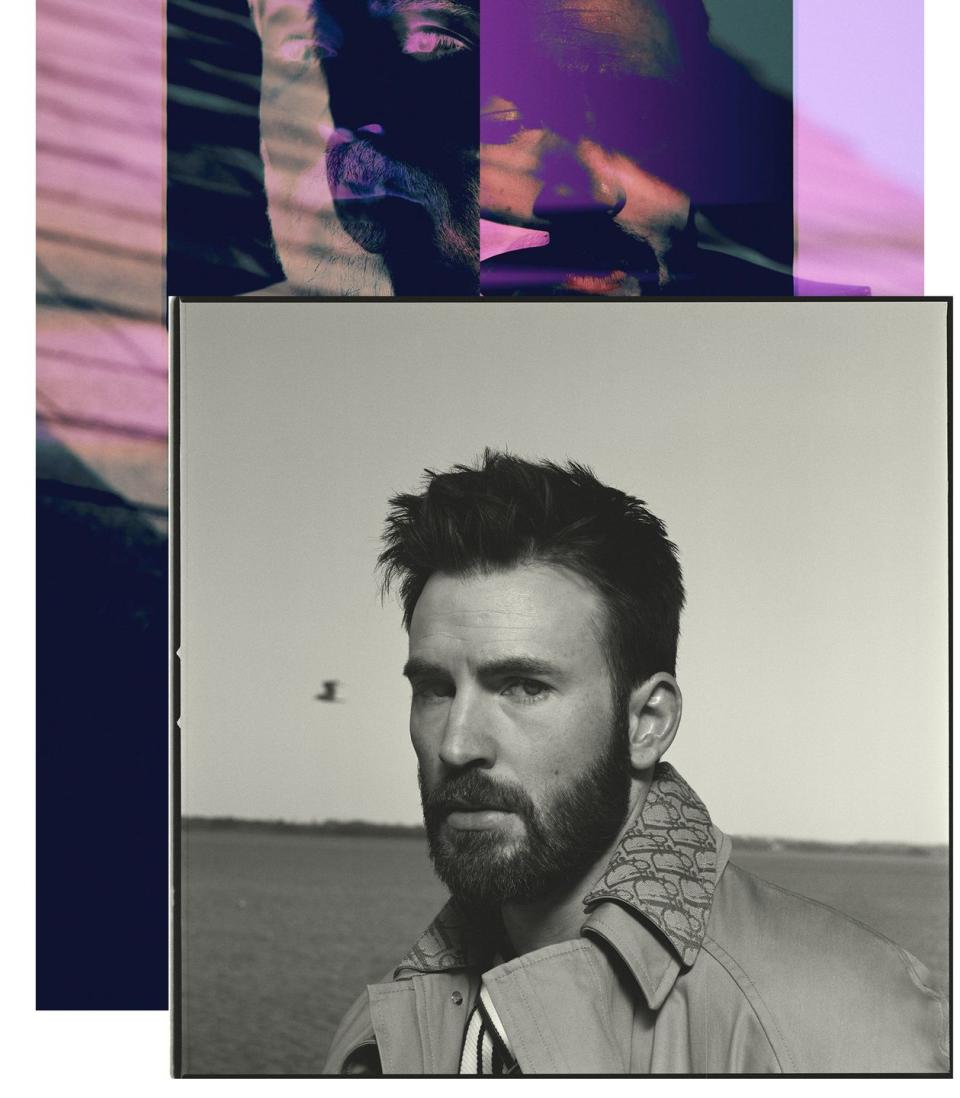

Evans is sitting in an armchair by an unlit fireplace in an area off the kitchen, an informal sort of room you might call a den. The furnishings appear to be mid-century modern, a style often seen in Los Angeles, where he has a house in the Hollywood Hills. Evans is welcoming but not warm, broish in a manner that bespeaks form over content. In person he seems very much like the guy onscreen; his upper torso is sculpted in a way that suggests he’s still wearing his Avengers uniform under his green tartan flannel shirt. His ball cap has a shamrock on the front panel.

Evans’s mutt is snoozing at my feet, letting out the occasional fart. His name is Dodger, after Evans’s favorite character in the Disney movie Oliver & Company—the roguish mongrel who leads Fagin’s gang of orphans. The pair met in 2016 at a Savannah rescue shelter where Evans was filming a scene for the feel-good movie Gifted.

You would never know it from the spotless condition of the premises, but last night Evans hosted friends for karaoke. I ask him his favorite song choice. “You can’t go wrong with Billy Joel,” he says. (Coincidentally, it was Joel who voiced Dodger in the animated film.) His lifelong crew includes a cardiologist, an engineer, a computer guy. Like Evans, they’ve made good but stuck around, rooted in their home soil, die-hard fans of the Red Sox, and the changing seasons.

Homebodies pic.twitter.com/b3s5BMcabP

— Chris Evans (@ChrisEvans) March 23, 2020

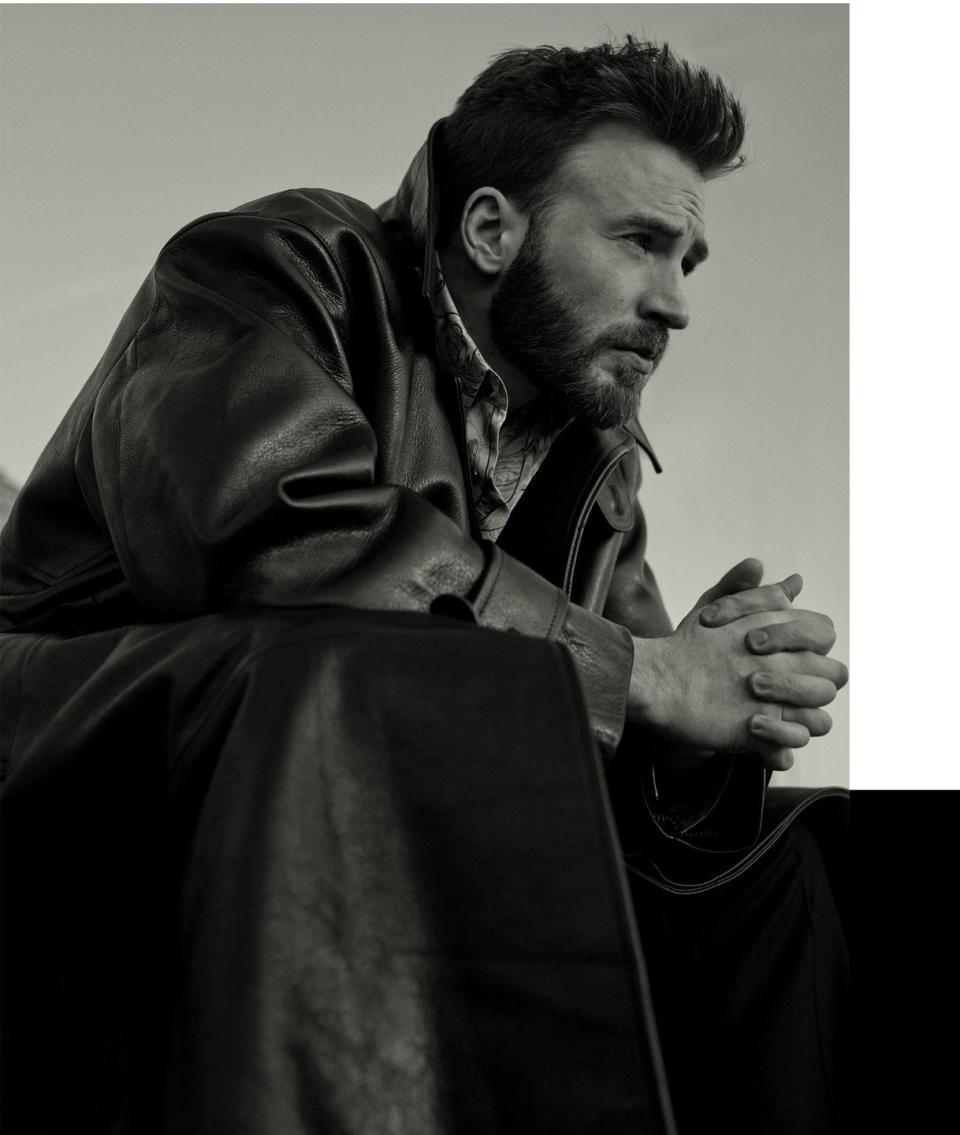

Evans’s latest acting project, Defending Jacob, is about to debut on Apple TV+. On the show, he plays an assistant district attorney in a small town who finds himself torn between his professional responsibilities and his love for his teenage son, who has been accused of a gruesome murder. As the episodes proceed, Evans’s character confronts his own secret past.

The limited series was shot in the Boston suburbs. “It felt like I had a regular nine-to-five job,” he says. “I’d sleep in my own bed; I’d see my family on weekends. A lot of times you have a bit of a nomadic lifestyle as an actor. You live out of suitcases and in cities you’re not familiar with. Doing Jacob made me feel like I was home but still doing what I love. It was incredibly comforting.” His real estate holdings notwithstanding, he considers this his home. He spends a lot of time with his brother, the actor Scott Evans (One Life to Live, Grace & Frankie); his younger sister, Shanna; and his older sister, Carly, and her children. He often calls his mom, Lisa, ten minutes before dinner to tell her he’s coming over to eat.

This article appears in the April/May 2020 issue of Esquire.

subscribe

We’re about halfway through our two hours together when I bring up some Hollywood gossip: Evans’s team is in negotiations for him to play the role of the sadistic dentist in a remake of the musical Little Shop of Horrors, portrayed in the 1986 film by Steve Martin. Evans mentioned his interest in the project last year. His only public acknowledgment of the recent news has been a mysterious tweet—a tooth emoji with an exclamation point.

He’s been acting since age nine, when he followed Carly into the Concord Youth Theatre. (When she was about twelve, Evans recalls, she starred in a production as Audrey, Little Shop’s female lead.) All four Evans siblings were active in CYT; eventually his mom became the artistic director. I ask him if his interest in Little Shop reflects a childhood love of musical theater.

A cloud descends over his face. His brow beetles. He shifts himself uncomfortably in his chair.

“It’s not like, ‘Oh, I love musicals!’ ” he says, throwing up a pair of jazz hands.

At first, I can’t tell whether he’s joking.

During my time with him, the same sequence will play out several times: I toss him what I think is a softball question . . . and suddenly he’s glaring at me like I’m Red Skull, Captain America’s Nazi foe.

Or maybe not Red Skull. But you get what I’m saying. He gives me an uncomfortable look that lets me know he’s not pleased. It’s like he’s just waiting, ready for it. What arrow will this guy sling next?

At thirty-eight, Evans is twenty years younger than I am. I’ve never had $70 million in the bank, but I have gone through many of life’s passages. For me, forty was a good age. I felt myself making new connections; things started to come together in a way they hadn’t before. But forty is a tough age, too. I realized I was pretty much halfway played. When that sneaks into your head, it doesn’t go away. Choices begin to feel more precious. You don’t want to fuck it up.

With Evans, I sense that I am meeting a naturally shy superstar who feels as if he’s done about a zillion too many interviews, as if he is always being boiled down into an essence that does not begin to accurately reflect his many nuances. His will to explain himself has worn thin.

His voice takes the tone of an overworked teacher trying to instruct a student who needs extra help.

“As a kid, theater is what’s available to you, local plays. And it’s usually going to be a musical. But musicals aren’t the thing that I fell in love with. I just liked acting. I have a soft spot for theater, because it was such a big part of my childhood, a very sweet chapter in my life. But it’s not like I’ve always said, ‘Man, I got to get back to musical theater!’ ” The hands again. “My main reason for doing it was because I liked acting so much.”

When we meet, Evans is counting down to the spring launch of his post–MCU passion project, a new political website called A Starting Point. It is meant to help inform and unify our divided electorate by providing a series of two-minute videos from elected officials. Organized by topic, it has opposing views conveniently juxtaposed. The basic notion: Exchanging ideas in a peaceful manner is a good way to begin to solve differences.

We move from the sitting area to the eat-in kitchen so that he can show me the site. His laptop is resting on a long, gleaming marble island. Across the room, I see the karaoke machine. I wonder fleetingly if he’d cleaned up a mess to prepare for my arrival. He may be on the Forbes list of the 100 richest celebrities, but he still seems like a guy who does his own chores.

The idea for A Starting Point began to take shape a few years ago, Evans says, when he was watching a news show and found himself wondering what an oft-heard acronym actually meant—he can’t remember now, but it might have been NAFTA, the North American trade treaty, or maybe it was DACA, the Obama-era amnesty program for people brought illegally to this country as children. Either way, Evans was stumped. When he tried to Google an answer, he encountered a morass of competing headlines and long, confusing articles. “You’re just like, ‘Who is going to read twelve pages on something?’ ”

The whole experience got him thinking. “It just was one of those things where you see a hole and you think, I have an idea to fill that,” he says.

Over the past year, Evans and his business partner, Mark Kassen—an actor and director he met on the set of the 2011 indie film Puncture—have traveled to Washington, D. C., nine times to film 160 elected officials, including Cory Booker, Mitt Romney, Amy Klobuchar, and Ted Cruz, who brought his eleven-year-old daughter and tweeted, along with a photo of the trio, that “introducing her to Captain America was pretty awesome!” Evans conducted all of the interviews himself.

Evans has received criticism for what some have called the naivete of his undertaking; it’s hard to fathom how a series of short speeches from career politicians would cast light on anything. He insists A Starting Point is simplistic by design, something on the order of Politics for Dummies.

Evans admits he felt a little out of his depth wading into the project. “We were just so aware of the fact that we weren’t in our lane. There was so much to learn, starting with the vernacular. Like, you don’t say the word politician; you say elected official.”

On a deeper level, he realized how much he didn’t know about politics. “It’s a very tricky system,” he says. “The simple fact that they have to be elected to stay in office. People want to say, ‘I’m going to go to D. C. to be a politician, and I’m going to live by my morals and principles, and everything will be okay.’ But once you’re there, you have to start playing this weird game of chess; you have to start measuring whether the juice is worth the squeeze. It starts with little compromises and justifications, and before you know it . . .” His voice trails off.

So far, Evans says, the majority of the interviews he’s done have been with Democrats. “A lot of Republicans didn’t want to sit with me,” he says.

Part of the reason, he supposes, is his social-media presence. He has more than thirteen million Twitter followers and a reputation for strongly supporting liberal causes. He’s called Trump a “dumb shit” and referred to Senator Lindsay Graham as Smithers, the character on The Simpsons. With the launch of A Starting Point only weeks away, and a deficit of videos from red-state lawmakers, Evans tweeted support for Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who accused her conservative colleagues on the Supreme Court of bias toward the Trump administration.

Despite the occasional lapse, Evans says he is committed to putting aside his personal views for the good of his project. “I’m going to take my foot off the gas [of social media] for a little bit until we get this thing up and running.”

Naive or not, Evans’s reasons for creating the site, in this era of discordance, are unassailably pure. “I just want to say to people, ‘You know what’s helpful?’ That’s the beginning of the sentence,” he says passionately. “The site is not an antidote. It’s not medicine. It’s not a cure. It’s not the solution. It’s just something I think is helpful. But one thing I’m really trying to stay away from is declaring, ‘This is what’s wrong with today.’ ”

Politics runs in Evans’s family. His maternal grandfather, Andrew Capuano, was an alderman and a career civil servant who was the head of the Massachusetts Department of Revenue. When Evans’s mom saw her son in Avengers: Endgame made up to look like an aged Steve Rogers, she burst into tears—he resembled his late granddad exactly. Evans’s uncle Mike Capuano was the mayor of Somerville. He served ten terms in the U. S. House of Representatives. (He lost reelection in 2018 to Ayanna Pressley, a progressive congressional freshman and a member of the Squad.)

Earlier, in the sitting room, Evans had told me fondly of his time “hanging out in [his uncle’s campaign] headquarters when he would run for reelection. My mother did a lot of stuff for it. I just remember those were fun chapters of my life—just being a part of putting flyers on doors and things like that, you know?”

I ask if his family background had anything to do with his decision to create A Starting Point.

The cloud again. The brow.

“Sure, sure, sure,” he says dismissively. He sees the connection I’m trying to make. He can already see the story I’m trying to tell. My angle. So many stories, so many angles, all of them a little bit wrong.

“Just to be clear,” he says, poking the air with his finger like a politician at a debate, “it’s not like when I was nine years old I was talking about policy with my uncle, you know what I mean? It wasn’t like, ‘Man, being around those campaigns really changed me!’ I would go with my mother to his headquarters the same way I’d go with her to the department store.”

Evans’s mother, Lisa Capuano Evans, is found in the basement of a beautifully restored church that is now home to the Concord Youth Theatre. She’s sitting in an overstuffed executive chair that looks out of place in the backstage setting, an accommodation for her bad hip. “I’ll be sixty-five in about three weeks. It’s over for me,” she says lampoonishly, her twinkling eyes the same blue as Evans’s.

After being housed in a series of spaces over the years, the company relocated here last fall, thanks to a contribution of an undisclosed sum from CYT’s most famous alumnus; Evans showed up personally to cut the ribbon. The stage of the two-hundred-seat theater sits in the approximate place where an altar once stood. “The first show we staged was Godspell,” Lisa says. “I don’t know, I thought it was funny.”

Evans says fondly of his mom, “She’s a nut. She’s a character in a movie.” Half Irish and half Italian, Lisa is outspoken and funny but also sentimental. She says her son inherited her “crying gene.” She grew up in Somerville and met G. Robert Evans III at Tufts University, where he was studying to be a dentist, she a dental hygienist. They had four children—girl, boy, boy, girl. Evans is the second. “I thought they were the most beautiful things on the planet,” Lisa says. “But really, they were just goofy looking, average. They all had crooked teeth and silly haircuts and dorky clothes, and they didn’t care.”

When Evans was in third grade, his family moved to Sudbury from a neighboring town. Carly, the eldest by three years, began taking classes at CYT. Soon after, her brothers began to agitate to join. “We’d come to see Carly’s shows,” Lisa remembers, “and the boys would say, ‘Wait a minute, we sit in the audience, and she gets to sing, she gets to dance, she gets to do all this stuff, and then afterward she gets candy and flowers and we take her out to dinner. We want to do this!’ ”

By the time Evans was a junior at Lincoln-Sudbury Regional High School, he was deeply involved in theater. “His focus became very myopic,” Lisa says. “The director of the drama program made the kids do Shakespeare and Dario Fo and Pirandello. Chris loved it. Even at that young age, you could tell he understood what he was reading. He would portray a character in a way that might be a little different than what you might expect. Just very interesting choices.”

One day, Evans came to her wearing a serious expression. “I know what I want to do with the rest of my life,” he told her.

That summer, he went to work for an agent in New York. His parents covered his rent. Using his new connections, he found an agent to represent him.

By January of his senior year, Evans had landed a role on Opposite Sex, a short-lived show that aired on Fox in 2000. He moved to Los Angeles and spent the next decade hustling for parts—a slacker jock in Not Another Teen Movie, Johnny Storm in Fantastic Four, a skateboarding foe in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. Then he got the offer to play Captain America, no audition necessary.

At first, he said no.

“His biggest fear was losing his anonymity,” Lisa recalls. “He said, ‘I have a career now where I can do work I really like. I can walk my dog. Nobody bothers me. Nobody wants to talk to me. I can go wherever I want. And the idea of losing that is terrifying to me.’

“He would call and ask for my advice,” she says. “I said to him, ‘Look, you want to do acting work for the rest of your life? If you do this part, you will have the opportunity. You’ll never have to worry about paying the rent. If you take the part, you just have to decide, It’s not going to affect my life negatively—it will enable it.’ ”

Back at home, Evans is talking about his character on Defending Jacob. He says he drew a lot from his close relationship with his dad, who encouraged him to play soccer and lacrosse in addition to acting. His parents divorced in 1999, just after Evans moved to Los Angeles to film the pilot for Opposite Sex.

“I was supposed to be G. Robert Evans IV,” he says. “I would’ve been Bobby, but my mother was in love with the name Chris. So my dad gave it to her.” After his father remarried, he started a second family. Evans now has a stepbrother named G. Robert Evans IV. “My dad was very happy to pass that on. I always wondered if I would have been a good Bobby. I’m glad I’m Chris. I would’ve been honored to have had that moniker, be in that lineage. But Chris is good, too.”

Evans says he might not have “lasted in this business without my father’s pragmatism and his curiosity. I think my dad’s level head is the thing that makes getting up every day possible for me.”

When Evans saw the final cut of Defending Jacob, he says, “it was a little disconcerting. A lot of scenes where I’m doing certain things, like, for instance, my character’s morning routine in the kitchen—there was the tie, the cup of coffee, and I was like, ‘Wow, I am watching my dad. I’m old.’ It just happened.”

With our time coming to a close, Evans suggests we let Dodger outside. The French doors open onto a stone patio bordered by a low rock wall. Dodger rushes past us and into the grass to do his business.

Looking for a way to sum things up, I tell Evans he kind of reminds me of a young George Clooney. It is meant as a compliment. Sort of like: He is a Clooney for a new generation—an affable, handsome, respected, and respectable male star with a great Q rating and a desire to do good works.

The cloud again. The brow. A look like he’s just tasted something bad.

“I don’t really think much about those things,” he says. “I actually think it’s a little bit of a slippery slope.”

And here we are again.

Maybe it’s nonsensical to ask such a question. Maybe I’ve run out of salient things to ask. I have watched all but three of his thirty-six movies. You do that, study someone’s work and life, and you grow somewhat fond of them, at least I did with Evans. And I want him to know my intentions.

“I’m not here to fuck with you,” I say.

“Okay,” he replies. “But that’s what this seems like.”

Evans hops up on the rock wall and begins to walk along the top, casually playing like he’s on a tightrope, the way people do.

He stops and turns. “I don’t put myself in a box. I don’t have some huge plan in terms of what my goals are. I just kind of wake up and follow my appetite. I’m at a point in my life now where I have the very, very fortunate luxury of pursuing what I want to do. And I don’t corrupt that process by thinking about how other people see me.”

Want Esquire delivered on the daily? Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

We stand a minute in the waning sunshine. Dodger trots up and takes a seat on his haunches on the grass nearby, posing like a statue, gazing solemnly outward. Before us spreads Evans’s front acreage. Surrounded by a weathered, split-rail fence, it slopes down a slight incline toward a rural lane.

“Look at that guy,” he says, nodding toward Dodger.

“I love the way he’s just sitting there,” he continues. “He’s just looking. He’s not trying to process. It’s like, the worst thing about people is the way we can see the setting sun or something equally beautiful, and for a split second it’s great—but then very quickly your brain wants to know, What does this have to do with me? And right away the greatness goes away.”

Evans turns to face me. “They say in Buddhism you need the boat to cross the river, but once you cross the river, you don’t need the boat,” he says. “This guy right here is a perfect being. Look at him. He’s not asking, What does this have to do with me? He’s just sitting there, experiencing what life has to offer. I’m trying to be the same.”

He hops off the wall and heads inside.

This article appears in the April/May 2020 issue of Esquire. Give the gift of Esquire by sending someone a subscription here.

You Might Also Like