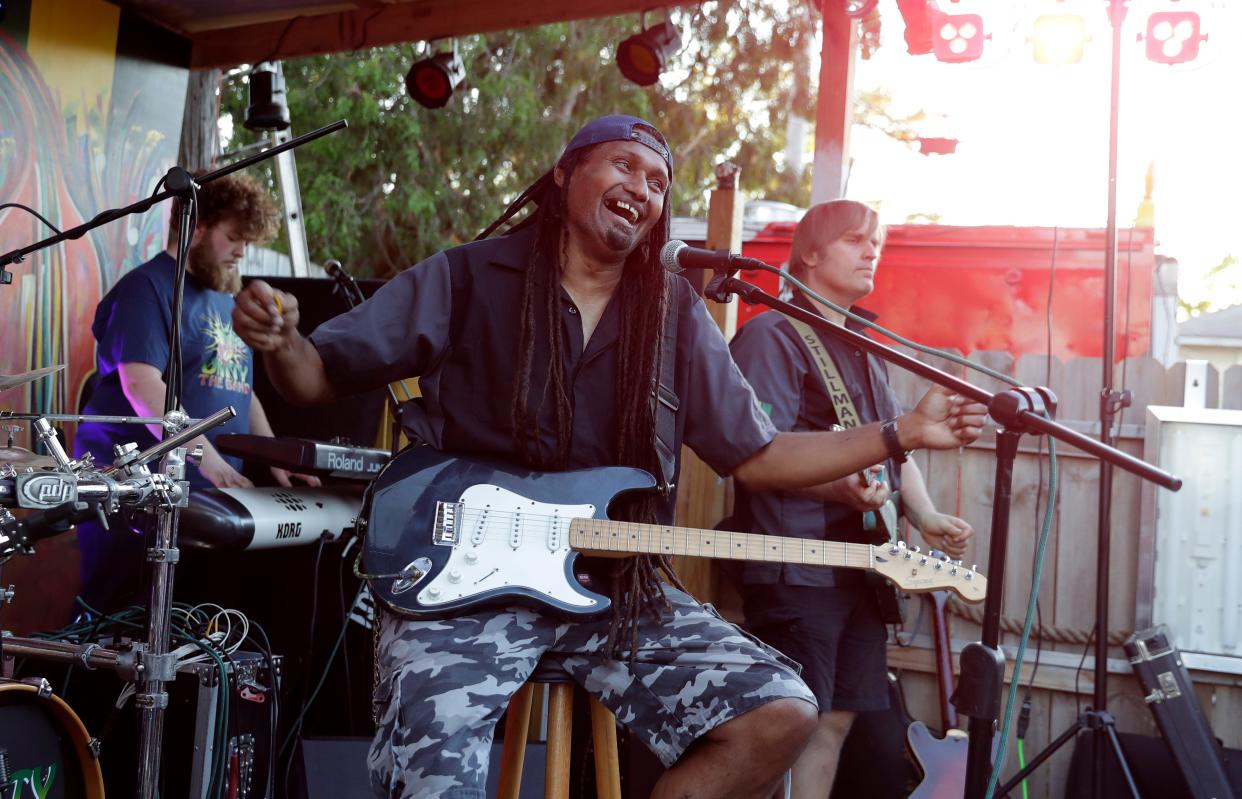

'He brought out the best in everybody': Pita Kotobalavu, the founder, frontman and huge heart of Unity the Band, dies at 55

It didn’t matter where Derron Wilson and Janel Johnson-Wilson traveled to hear Unity the Band — Florida, Door County, Appleton — or how many people were there, frontman Pita Kotobalavu always gave them a shout-out from the stage.

“Lil Jamaica in the house!” he would say, with a smile that could light up a crowd.

“It kind of made you feel special,” said Wilson, who owns Green Bay’s Lil Jamaica restaurant, lounge and food truck with Johnson-Wilson. “He had that about him. He had that thing, that special little touch that not everybody has. That one person that could make everybody feel like they belong. He brought out the best in everybody.”

It’s why his death on Saturday at age 55 from colon cancer leaves not just an irreplaceable hole in the Wisconsin music scene, where Unity’s reggae shows have been a beacon of unbridled happiness, escape and uplift for 23 years, but also a hole in the hearts of anyone whose life was ever touched by his spirit.

He radiated positivity, peace, joy, kindness — all the words repeated over and over in the condolences on social media as the news of his death spread.

“The most important thing in the world is love. People love to love,” Kotobalavu told the Green Bay Press-Gazette in a 2022 interview. “... Our music has always been based around that.”

His own loves were many — the Fiji Islands where he grew up with little but got his introduction to music; Wisconsin and the opportunities it afforded him when he moved to the state in 1999; his children, Sebastian and Melanie; his domestic partner of 14 years, Kay Halbrook, and her children, Grace and Ian; rugby, both as a former coach at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point and a player in the Fox Valley; and, of course, his band.

He founded Unity in 2000 and during its more than two decades, the Fox Valley-based band packed venues across Wisconsin and beyond with a rigorous schedule of shows sometimes five or six nights a week during summer. The group won more than a dozen Wisconsin Area Music Industry Awards, including the top honor of Artist of the Year in 2021.

For Kotobalavu, a self-taught musician who was 10 when he discovered Bob Marley and the Wailers' "Soul Rebel" album, it was always about the larger vision of what he could do through his music. Events like the annual Midwest Sunsplash music festival he and Halbrook put together for years, often in Menasha, as a benefit for Youth Go, a nonprofit teen drop-in center in Neenah near their home on Doty Island.

“The next big, exciting thing he could do to make the world a better place, he was all about that,” Halbrook said.

“He never cared about the little details, like are we making money, are we going to get rich, are we going to win awards? None of his points of views were like that,” said Tim Perkins, who has been Unity’s bassist for the last 10 years. “They were all about trying to do something good for people. He saw the bigger picture of what he wanted for the world and the crowds could all feel it."

At 55, he was just getting started.

Money he made from band went to his village in Fiji, charity

In the last few years, he had begun to rejuvenate his grandfather’s farm in Fiji in hopes it could help sustain the small village nearby. He and Halbrook had planted 12,000 coffee plant seedlings, and Kotobalavu bought 30 goats for the village. Just days before he died, he bought three calves to add to the dozen head of cattle there.

The couple were last back there in February. Kotobalavu was the leader of his family, and anytime he visited, it warranted a big celebration.

While there, they bought all 15 of the young rugby players who work at the farm new rugby shoes. They couldn't afford their own, so they had been sharing shoes, handing them off as one player came off the pitch and another ran on.

“You would’ve thought we had given them bars of gold. They were so happy. It was just amazing,” Halbrook said. “That’s the kind of person he was. Anything Pita made went either to a charity or his village.”

His “soft spot” was helping kids ages 15 to 25. More than once, if a foster child got kicked out of their foster home in Wisconsin and needed a place to say, he would invite them to stay in the couple’s basement.

It was Kotobalavu who encouraged Wilson several years ago to start his own food truck to serve his authentic Jamaican cuisine, after the two strangers struck up a conversation one night while Wilson was cooking jerk chicken on a grill outside a bar Kotobalavu was playing.

When he opened Lil Jamaica, Wilson invited Unity to be the house band and play monthly out in the beer garden. Kotobalavu was one of his greatest supporters, helping however he could to get the small business off the ground.

“He was just a good friend. He would play there, but he wouldn’t even charge me the same amount of money he charged everyone else,” said Wilson, who grew up in Hanover, Jamaica.

“You’re my brother, man, and you’re from the island, just pay the guys and I’m good,” Kotobalavu would say.

No matter how much Wilson insisted, Kotobalavu wasn’t having it. Wilson would feed the band when they gigged there as a show of appreciation. Then finally last year he told his friend that with Lil Jamaica well-established it was time to let him pay him his due.

“You see where I’m at now? You did it. You helped me already. I’m good, Pita,” Wilson told him.

Kotobalavu allowed him to pay him more than before but still not the full amount.

Those Unity shows at Lil Jamaica became special. They were both loose and incredibly tight. The band would play for four or five hours and take just one break. Wilson would sometimes get up onstage with a box on a pole in the very late hours and put it over the light so it didn’t shine in the beer garden. It’s similar to something they do in Jamaica to cover the streetlight and then have the music play down low. Kotobalavu would have the band break into the “Mission: Impossible” theme.

“We used to say you haven’t seen Unity play if you haven’t seen them at Lil Jamaica,” Wilson said. “It was just a different vibe.”

It was only a couple of weeks ago that Kotobalavu stopped in at Lil Jamaica to bring Wilson a sound system for the lounge. He had told him he was sick months earlier, but not wanting to believe it, Wilson had pushed it out of his mind. When Kotobalavu left the lounge that day, something felt different.

“When he hugged me, it didn’t feel like all the hugs we shared before. It felt like a goodbye hug, like I’m never going to see him again,” he said.

He was determined to play through the chemo, make final gig

Kotobalavu was diagnosed with colon cancer in June 2022 and went through extensive chemotherapy. It was his wish to keep it mostly private. Halbrook thinks he didn’t want to cloud the fun that followed Unity wherever it went.

The toll the disease took on his body did require, however, that the band scale back its ambitious playing schedule. They performed 125 shows in 2023, down from the years when they pulled off 180 or more, but still as busy as most any other band.

Kotobalavu’s bandmates and others jumped in to make sure he never had to lift any of the equipment or be at gigs for any longer than the time they were onstage.

“Especially the last six months, that was what it was all about, how do we just give him everything we can?” Perkins said.

Last May, Halbrook and Kotobalavu flew down to Alabama and drove back an RV so they could be together out on the road during gigs that summer. She was able to work remotely at her job at a sales brokerage company in Appleton and still be there to support him. They brought the dogs. It felt more like home than hotel rooms.

In those crazy weeks when they found themselves driving from Milwaukee one night to Phelps the next to Door County the next, the running joke between the two of them was: “Who in the world booked this schedule?”

It was, of course, Kotobalavu, who booked all the band’s dates and never wanted to say no to anybody.

“He played a lot of shows with his chemo pump on his body. He didn’t want to stop,” Halbrook said. “It rejuvenated him to be in front of people. It was not easy for him. He would be literally collapsing getting into the van at times. It was hard, but he loved it. He really loved it.”

Music was a welcome distraction from the disease. He fought hard to play the final scheduled show on New Year’s Eve at Peach Barn Farmhouse & Brewery in Sister Bay. It was billed as Unity the Band’s retirement party. He performed a half-dozen of his favorite songs from a chair.

“It was a wonderful night for him,” Halbrook said. “The people in Door County always just adored him. He could have sat there and stared at the crowd and they would’ve been happy.”

His ability to connect with people, stir up a crowd was special

Kotobalavu was driven to make Unity a success, and it didn’t come without tremendous work. He talked in interviews about how in those early years when he went to venues to seek gigs, he was told “your kind” wasn’t welcome there. He looked at those instances as a chance to find common ground. He was just an island boy who grew up on a farm, he would tell them.

“After you have a few sit-downs and talk, the next thing you know the door is open,” he told the Press-Gazette in the 2022 interview. “When you show love, you have to educate at the same time.”

He knew playing Bob Marley and cover songs came with the territory to keep crowds engaged, but he loved mixing in his own songs, too. He built a full recording studio in the basement of their home where the band rehearsed. When he wasn’t performing, he would often go down there and “noodle around” on the keyboards, write and record.

He wasn’t afraid to experiment on different instruments, come up with new sounds and blend different genres into Unity's reggae, said Perkins, who had developed a secret language of onstage looks and hand signals with him after a decade of playing together that only the two of them could read.

As a frontman and entertainer, he became almost a different person when he got in front of an audience, Halbrook said.

“You would never see anyone that could stir up a crowd like he could,” she said.

“He did have a way of connecting with people that no one else that I’ve ever met has possessed, and that was one on one or one on a thousand,” Perkins said.

“He just had a way of communicating with everyone and kind of letting everyone know this is going to be a happy and safe space for everyone. It was deeper than just a vibe. It created an entire culture.”

He used the stage as a platform and sometimes would talk during shows about what was important to him, whether it was women’s rights, inclusion or peace.

“He let people know what he was about, and that is what really built the crowds and built the fanbase, I think, is people who wanted to be in that type of environment,” Perkins said. “I think he would want the message to keep going.”

Wilson knows fans at some of Unity’s final concerts might have wondered why Kotobalavu — a man who made friends with everyone, no matter age, color of their skin, where they came from or how much money they made — would stop the music and take 10 or 15 minutes to talk to the crowd about loving and respecting one another.

The reason was simple: He wanted it to be his legacy.

“If a lot of those people just took the moment to ... listen, he was actually saying goodbye,” Wilson said. “That was his last wish for everybody that knew him was to find the humanity in everything and just live and spread love and spread the message of music.”

A celebration of Pita Kotobalavu's life is being planned for April 21 at Fifth Ward Brewing Company in Oshkosh. It will include a fundraiser for some of his favorite charities, with details to be made public at a later date.

Kendra Meinert is an entertainment and feature writer at the Green Bay Press-Gazette. Contact her at 920-431-8347 or [email protected]. Follow her on X @KendraMeinert.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Pita Kotobalavu, founder, singer and heart of Unity the Band, has died