The Boy and the Heron review: "Miyazaki proves he's still a master of the medium"

The Boy and the Heron has just had its North American premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. Here’s our review…

Animation maestro Hayao Miyazaki has been threatening to retire for some time now. Ten years ago, The Wind Rises was set to be his swan song, but he has returned with The Boy and the Heron, which may or may not be his final movie (reports are already circulating that he might be coming up with more ideas for Studio Ghibli, the anime powerhouse he co-founded).

If this is indeed his last film as writer/director, it’s a fitting send-off. It’s a testament to his mastery that the film opened in Japan with an unprecedented lack of pre-release promo, and still stormed the box office. Around the world, Miyazaki’s name is synonymous with virtuosity and imagination, and it’s unusual to find someone working in animation who doesn’t cite him as an influence.

It would be all but impossible for The Boy and the Heron to soar as high as Miyazaki’s most celebrated works (My Neighbor Totoro, Spirited Away), and so it proves. But that's hardly a damning statement about a film chock-full of heart and whimsy. The film manages to be in the tradition of his previous works, without feeling like microwaved leftovers.

Familiar ingredients you expect are present and correct: the impact of war, a childhood interrupted, a retreat to the countryside, fantastical creatures, caricatured grannies… Here, the child who’s forced to reckon with all life's uncomfortable offerings is Mahito. Set during the Pacific War, the film boasts a kinetic, expressionistic opening that sees flames rain down, and the hospital where Mahito’s mother is staying is destroyed.

A year later, Mahito and his father, Shoichi, move to the countryside, and we’re introduced to Shoichi’s new wife, Natsuko, who happens to be the younger sister of Mahito’s late mother. At the estate where they now live, Mahito - who’s struggling to fit in at his new school - starts being pestered by a grey heron...

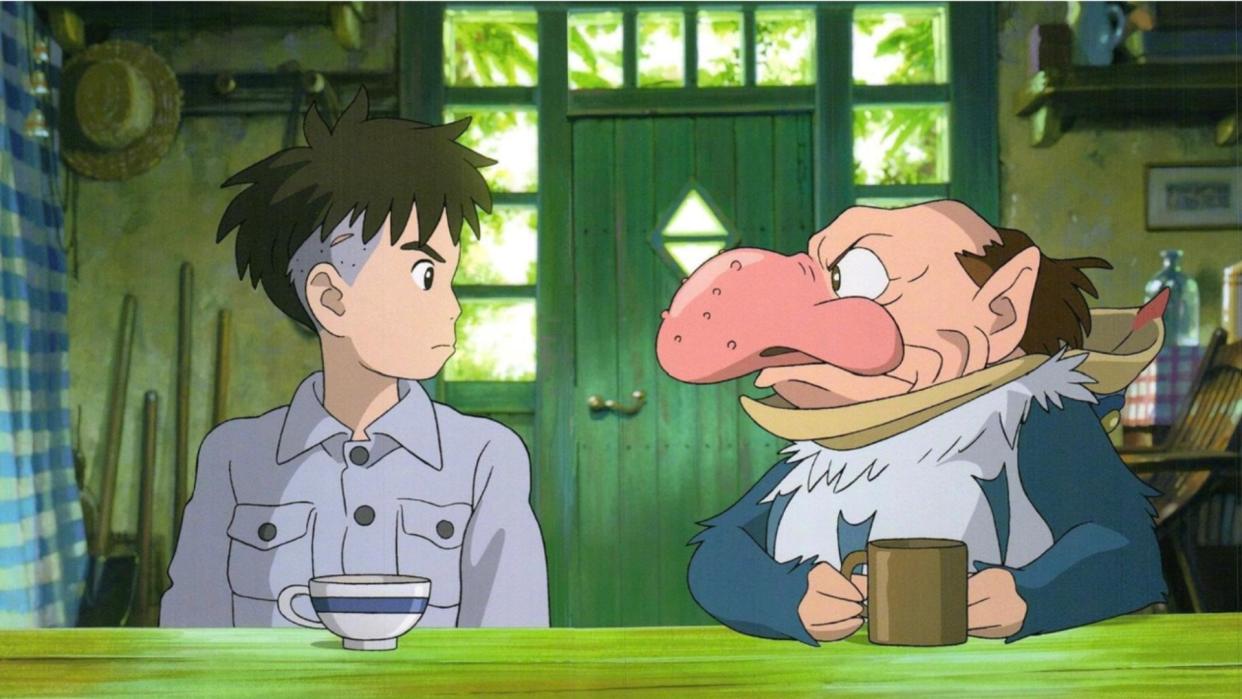

This will eventually lead Mahito to an alternate wonderland, on a search for both his mother and Natsuko, who has also gone missing. Anyone familiar with Miyazaki’s previous work will have an idea of what to expect from the upside-down world. There are creatures both cute and grotesque. The warawara are adorable sprites that look like bipedal marshmallows. The heron, meanwhile, proves to have a man living inside: occasionally just his teeth are visible under the beak, while sometimes his whole gnome-like head is visible, like a football mascot taking a breather.

Another highpoint of the alt-world is an army of bulked up parakeets, who provide much of the threat and humour. This being a Ghibli joint, even on the fantasy side, the imagery is often visceral, from a fish that’s gutted in organ-spilling style, to characters - including our young protagonist - who bleed in a way that really stings. In this world, simply being cute won’t stop you from being gobbled up by a pelican, and, as in the real world, birds shit. A lot.

It goes without saying that even the more unpleasant imagery is rendered in stunning style. You could freeze any frame and slap it straight on your wall. The pastoral backgrounds frequently look like oil paintings. Characters move with quivering naturalism, hair always in motion, clothes ever creasing. Being able to surrender to the imagery in this way helps to maintain engagement when some of the story’s fantastical plot elements become a little baffling in places, and arguably mute some of the potential emotional power. It’s an easy film to go along with, even with those quibbles.

If it does prove to be Miyazaki’s last bow, it would be a thematically fitting send-off. There’s a reference to a book called ‘How Do You Live?’ (which is also the film’s title in Japan), and that question proves both pertinent and poignant. It’s easy to imagine that future analyses will see Mahito as a stand-in for Miyazaki himself. Whether or not that’s actually the case, it’s always going to be hard to disentangle the film from the filmmaker here. If this is a farewell, it’s an extremely fond one.

The Boy and the Heron is released in US cinemas on December 8. Its UK release date is TBC.