THE BLACK GUY DIES FIRST Authors on Their Horror Loves and the Genre’s Future

In 2019, the groundbreaking documentary Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror gave us a vital education. Based on Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman’s 2011 scholarly text Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present, it resonated deeply with Black horror fans, teaching us something new about a genre that we all have a complex relationship with. For those of us who have been into horror for a while, our resources prior to Horror Noire included sites Mark H. Harris’ Blackhorrormovies.com, a digital Rolodex of films by and about us. It has the perfect blend of humor, information, and analysis about horror’s Black flicks over several decades.

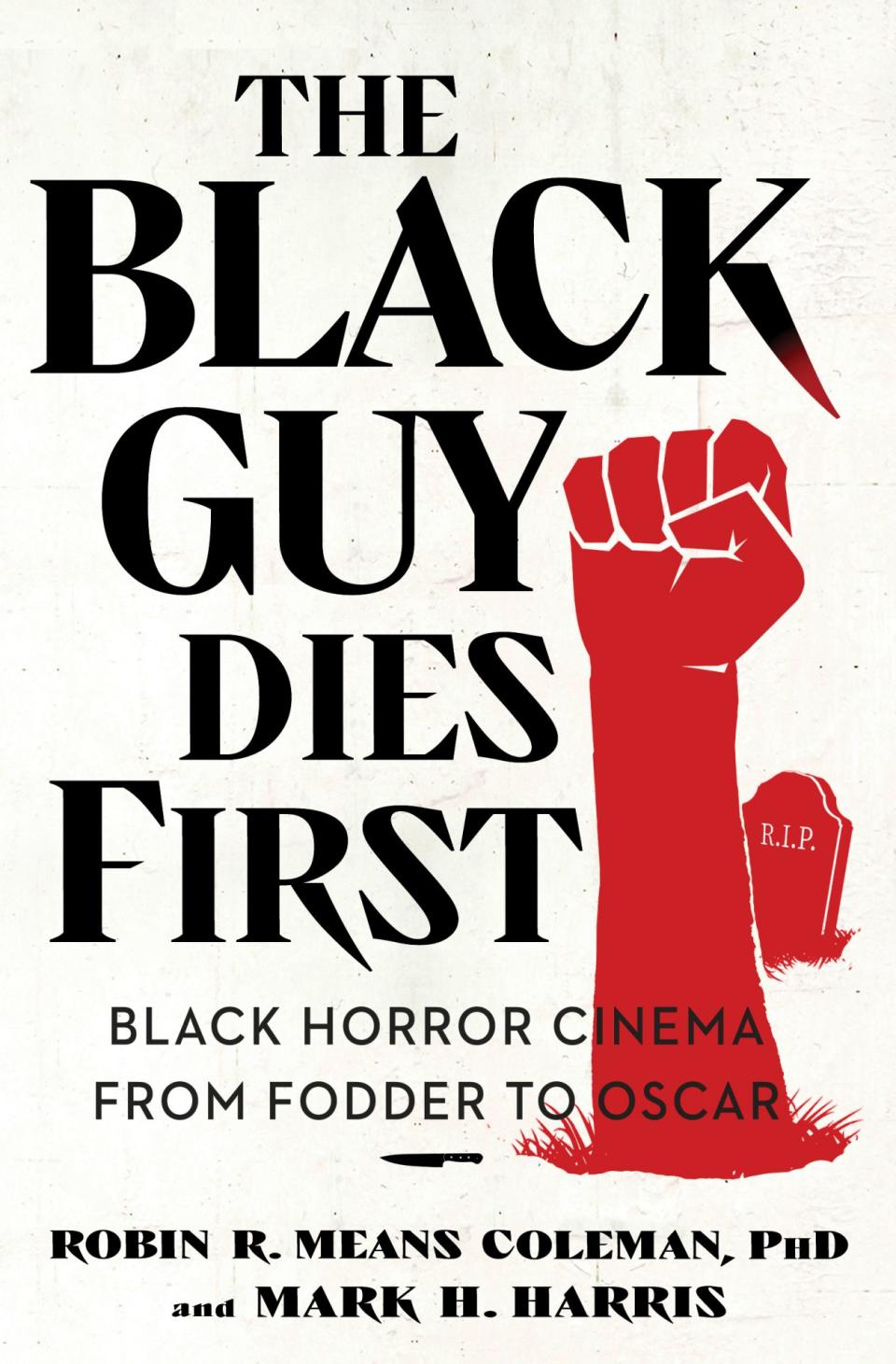

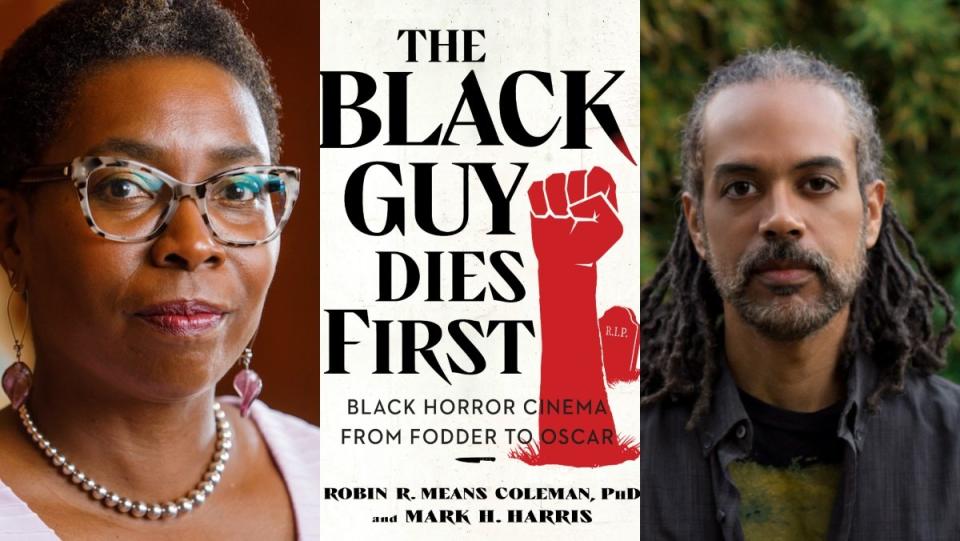

Now, Dr. Coleman and Mr. Harris have joined their brilliant minds together to bring us The Black Guy Dies First: Black Horror Cinema from Fodder to Oscar, a brilliant exploration of Black horror to add to your collection. (Let’s call it The Black Guy Dies First for brevity’s sake.) Nerdist caught up with the authors to discuss the book, their gateway into horror, and hopes for the genre’s future.

Nerdist: What drew you into the world of horror?

Mark H. Harris: Well, I’ve kind of always been interested in the darker side of storytelling. One of the earliest horror movies I remember watching was Night of the Living Dead. And I was fascinated by the fact that the main character was a Black guy. And it was a black and white movie, which to me seemed ancient. So the fact that the lead character was this Black guy who was bossing white people around and slapping them and stuff, and he was the hero of the story was really fascinating. Then, on top of it, he ended up dying at the end.

It really struck me as a child… I think it was probably 12 or so when I watched it [for the first time]. It reflected the realities of life. Not everything has a happy ending. And you can tell a story that’s a great story and not have the people walk into the sunset and everything be great. That’s kind of what horror does. It looks at the darker side of life and how things don’t always have happy endings. And it just really resonated with me. So that sent me down the horror spiral, I think.

Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman: Romero is going to loom large in this first response. I was born and raised in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. My family is still there. And that’s obviously where Night of the Living Dead and the Dead films were filmed in or around. So there was this sort of omnipresence of Romero growing up. He was at Carnegie Mellon University and I was even a student at CMU. At one point, it sort of felt like, “Oh, I’m walking in the footsteps of George Romero.” …There’s something about Night of the Living Dead.

And I will have to admit that much later than most [people], I didn’t quite understand it as a proper horror movie because I was so focused on the character Ben, portrayed by Duane Jones, and what was happening there. I didn’t have that language at the time, but it felt very ethnographic. Night of the Living Dead has real Pittsburghers in it that other people may not know, but we recognized them. And so it sort of hit different for Pittsburghers. That [film] was probably my introduction to social justice questions. Understanding that there were narratives about anti racism that we should be engaging with. So that is how I got into it.

That explains why this film is such a cornerstone in your work! It was truly revolutionary at the time.

Coleman: Yes… Ben represented something else that was so powerful. Now, horror has been with me for so long. And there’s a blurring of genres for me, because we talk a lot about horror. And sometimes people are so serious about the horror genre. Horror is super funny. And I write a lot about comedy and I laugh until my cheeks hurt sometimes with these horror films. And so in that way, because I don’t fully immerse myself in the super gross out horror, it’s easy for it to be in my life because it’s super entertaining.

Absolutely. When it comes to The Black Guy Dies First, it feels like a continuation of what we saw in the Horror Noire books and documentary, both of which are vital additions to Black horror history. How do you think this book expands on that previous work and adds something new to the conversation?

Harris: I think it serves as a good companion piece to Horror Noire. It’s designed to be a little less academic [than the book] and have more popular appeal. It has more humor and little lists and sidebars and stuff but it doesn’t touch on a lot of the same topics… We’re taking more of an entertaining kind of aspect to kind of draw people in before we drop the big message.

I love the marriage of humor and knowledge. The Black Guy Dies First has a universal appeal in many ways, but some of the humor is absolutely for us. It’s so enjoyable and meant for only us to understand. Robin, how do you think that it really expands on Horror Noire?

Coleman: Mark is absolutely right. And Mark has been so deeply involved, including the second edition of Horror Noire, which came out in November, more than 10 years after the first edition. So it was happening at the same time as The Black Guy Dies First and there was a lot of conversation. The first Horror Noire is very much a scholarly text. There’s a significant theoretical, undergirding there, there’s a different reliance on data, the audience and readership is different, even though I can’t get away from the accessible tone in my writing in some ways, which makes it a popular text to be adopted in the classroom.

But Horror Noire is very US based and though The Black Guy Dies First focuses a lot on US cinema, because that’s what we know, I would say that we’ve done a good job of also gesturing outside of US bounds. And you’re absolutely right, this is a FUBU book. It’s for us by us… But I also do think it’s clearly a love letter to the genre from two people who are big fans.

Yeah, and there’s so much encompassed in about 300 pages of content. How did you two partner together to tackle such an expansive project?

Coleman: it really all starts with Mark’s Blackhorrormovies.com website. Mark is a horror scholar, super smart, and has a really nice writing style that is accessible. That is what the framework of The Black Guy Dies First is. And I relied heavily on his website as a resource to write the first edition of Horror Noire. There’s so many voices out there who will dissuade you from taking horror, particularly Black horror, seriously.

But Mark’s website isn’t just a laundry list of films. He’s got an encyclopedic knowledge and the way that he’s writing about the films on that site lets you know that he’s a brilliant scholar who understands the genre in front of and behind the screen… And then I totally turned into a fangirl and called him and said, “We got to do something,” and it was out of the blue… And it actually happened. So I’ve been in his life as a sort of writer-scholar for almost a decade. And I knew—he might have not known—but I knew that eventually we were going to partner on a project together because he is really a smart, gorgeous writer. And so I think that’s my definition of the process. I’m sticking to it.

There are so many Black writers who looked to Blackhorrormovies.com for inspiration and guidance, myself included!

Harris: Yeah. I think Robin definitely has the drive that I did not have. If it wasn’t for her, I would still be sitting on my sofa just writing for myself, basically. But I think she kind of pulled me into this world and made me realize that it is possible for us to write an actual book. Like, I never envisioned that I would write a book. Even on my website, I was just doing it for fun… I think it goes to show that you just write about what you like, you know, find your own little niche, and then things can happen for you.

Coleman: There’s a lot more books in Mark and a lot of great ideas. So we’re not done hearing Mark’s incredible voice!

I certainly hope we get more! Let’s dig into a book just a bit. In chapter three, you get into horror that’s infused with social commentary and analysis. I love the line where you say “Black horror is our social syllabus.” I’d love to hear both of you expand on that statement.

Harris: That was your line [Robin]. That was a good one.

Coleman: I want to preface by saying that I’m not saying every horror movie needs to be a message movie, and it doesn’t need to always center either black trauma or struggle… I’m not saying that. But the pure existence of Black horror in some ways is an intervention on those systems and structures that confined Blackness in the first place, right? The horror genre often allows us to break out of that. What I find really interesting is that if it’s a US horror movie, most often you have to reflect on the trauma, not the torture porn trauma that people talk about with slavery, but the institution of racism in the US in the first place. It looms large in Black American stories.

And so Black horror often turns kind of pedagogical. That social syllabus is not only an examination of those structures, but it also offers solutions, which I love. And in horror, the solution isn’t always simple. In fact, the solution in horror is wholly uncivil in its approach. And so we learn a lot about the civil rights movement and civility and respectability, and how to show up. And Black horror was like, “I see you, respectability politics, and I’m going to throw that out, and I’m going to eviscerate you.” And these are the powerful, symbolic solutions to a country that hasn’t always loved us.

All of this. Absolutely true. Mark, what are your thoughts?

Harris: I think horror in general has always been kind of a metaphorical genre that will often have deeper meaning beneath the surface. The monsters might represent something else. [With] Dawn of the Dead, there were a lot of messages about consumerism, you know, and Rosemary’s Baby was talking about the role of women. So I think when you infuse race into it, like you said, it’s kind of part and parcel with American society, everything to do with America has race, we’ve woven into the fabric.

I think when you have race in horror, it will inevitably—even if it doesn’t mean to—have some sort of social impact. Just the image, for instance, of a Black person being killed in a violent manner will trigger some people to say, “Oh, this is too close to home, too close to instances of police brutality.” So it’s always some sort of social inclination to imagery of Black horror, whether or not it’s really intended.

Yeah, for sure. And there’s also intersectionality within our identities, too. One of the things that you cover in the book towards the end was LGBTQ representation in horror. The pitfalls are disheartening, because I see horror as something that is very othered and outside the “norm.” So it is kind of inherently queer by definition. What do you think about the shifts in Black LGBTQ characters and do you think it will improve in our current landscape?

Harris: I think we’re at a crossroads right now with Black horror in general. It could go in a number of different ways. This whole resurgence of Black horror really kicked off in 2017 with Get Out, so we’re at the five or six year mark, where historically things can either fade out like the Blaxploitation era or the ‘90s urban movie era when Hollywood eventually found something else to pay attention to. Or [Hollywood] can find new voices to carry on… We’re at a key moment right now where we need to have voices who are willing to support Black queer stories and have studios and distributors willing to give them a chance.

It’s so important to see that representation in mainstream media. Yes, we do have lots of indie creatives who are making excellent and diverse content, but the mainstream still matters. Those films get big budgets and marketing and open doors for more stories.

Coleman: I think you’re absolutely right. I’ve pointed to technology as the next frontier. People have better access to digital technologies, and they’re saying, “We’re not going to wait for Hollywood, we’re gonna make our own.” That’s incredible but diversity in sexualities and genders needs to be mainstream and accessible, they can’t sit in the indie realm.

Right. Now that we are in this new and hopeful era, what do you want to see in Black horror?

Harris: I just hope that we get more voices. Right now, Jordan, Peele is kind of the dominant voice, and he’s kind of the representation of all Black horror. And I think there are so many other voices out there that can be elevated as well. Other than him, there haven’t been too many regular Black directors, in the horror genre, that have gotten a lot of publicity and mainstream release… But, thanks to Jordan Peele, hopefully people realize that the genre can be taken seriously. It can win Oscars, if it’s nominated. And it can be artistic and break grounds… Hopefully, studios will stop looking for “the next Get Out” and have a broader vision about how Black stories can be told.

Coleman: I have to pick up Mark’s thread. I don’t think every Black horror film has to be pedagogical and our social syllabus. Rachel True said it best in the Horror Noire documentary: “Everybody lives or everybody dies.” And that encapsulates what I want from my Black horror. Sometimes I just want it to be horror. I want it to be entertaining, it doesn’t have to be deep social commentary. There are so many inventive stories that are rooted in Blackness that can be told, and I’m waiting for that. And it doesn’t all have to be Get Out. It doesn’t have to be powerful social commentary, elevated horror, all of that… Sometimes it can just be everybody dies.

The Black Guy Dies First is currently available for purchase.