Ben Stiller Sees the World Differently Now

He walks through the door into the apartment where he grew up. The apartment is empty, which is strange but also kind of beautiful, seeing it clean like this. The parquet floors shine in the winter sun. Today is Sunday. In two days the sale will close, and the apartment his parents owned for fifty-six years will belong to someone else.

Fifty-six, the age he is now.

His sister, Amy, was with him today for a while, and they sat on the floor in their old rooms. As kids they used to knock on the walls to each other at night, in a secret knocking language.

He has children of his own now, who are flying through their teenage years.

When he was little, Ben would lie under his sheets after bedtime listening to music on his clock radio. WNYC had a program called While the City Sleeps, hours of classical music that made him feel as if he were floating. He always felt like he was getting away with something, listening to it. The city was asleep, but he was awake! He would stare out the window at the lights glowing in the apartment buildings up West Eighty-fourth Street. The city lights seemed to trickle up into the stars, and with the dreamy music playing softly—it was magical.

On Christmas Eve, he would look up into that sky for as long as he could keep his eyes open, trying to spot Santa’s sleigh.

Some nights he would hear his parents working in what the kids called the Big Living Room—which, walking through it all these years later, doesn’t seem so big. His famous parents, the husband-and-wife comedy duo, working on their act or writing commercials or whatever else they did in there while Ben was falling asleep. Stiller and Meara. A household name. Dad and Mom.

He’s working on a documentary about his parents. Their brilliance, their humor, their generosity, their struggles. It brings up memories of all the times they were there for him, and the times it felt like they weren’t, and how he thinks about that with his own kids. This apartment was always here, and they were always here, and he could always come home, even when he didn’t want to because he was out chasing his own dreams.

But the documentary is a good year away from being done. First he’s got to finish directing this nine-episode show for Apple TV+, Severance, which has taken forever because of the pandemic but which is finally looking just how he wants it to—a show he’d want to watch.

About those dreams of his: They’ve evolved. In 2014, he was treated for an aggressive form of prostate cancer. In 2015, his mother, Anne Meara, died at age eighty-five, after having a serious stroke. The following year, Zoolander No. 2 flopped spectacularly—and while the failure of a zany comedy isn’t a tragedy, especially compared to losing one’s mother, when it’s an international spectacle that you conceived, wrote, directed, starred in, and produced, and it seems like the whole world is watching it fail, it is, Stiller says, “not a great experience.” In 2017 his seventeen-year marriage to Christine Taylor unraveled, and they separated—and because they’re famous, it felt like the whole world was watching that, too. His father, Jerry Stiller, died in May 2020 at age ninety-two.

Before all of that, before any of that, Ben Stiller had achieved all the success a person could want, and more. He got a dream job at twenty-four writing for Saturday Night Live only to leave it after four episodes, co-created The Ben Stiller Show, directed Reality Bites, starred in There’s Something About Mary and became Gaylord Focker and Derek Zoolander and the Dodgeball guy, stole his scenes in a seminal Wes Anderson film, cowrote and directed and starred in Tropic Thunder…

It was a pretty amazing run. And there was a clarity to it all. He worked hard, pursued satisfying projects, and repeated the things that worked. He made Ben Stiller movies. He was always ascending. Then, starting with the cancer, he got the crap pounded out of him for a few years. His career, his marriage, his parents, his own mortality—the underpinnings of his whole life cracked, and nothing seemed clear at all anymore. And what does a person do then?

Well, then the pandemic happened.

He opens the door to his old home, steps out into the hall, hears the door clunk closed behind him one final time. Then, on his way to the elevator, he stops. He turns around, walks back toward the door.

One more thing, he thinks.

He steps back inside the apartment and pulls out his iPhone. He presses the camera icon on the screen, swipes it to Video, frames the shot, and presses Record.

“Right there!”

Stiller is sitting in a darkened editing room in New York, looking at a screen on which John Turturro’s head is enormous. Turturro is one of the stars of Severance, and Stiller and his three-person sound crew are mixing the sound effects for one of the episodes. Stiller and editor Geoffrey Richman are working from notes scrawled on pads denoting time stamps where something needs adjusting. “Let’s see: ‘24:17, Irv car noise,’” Stiller says to the room. “Oh yeah, the car stopping.” At this mark, the car Turturro’s character is driving lurches to a halt, and—in Stiller’s estimation—the quick screech it makes is too loud.

“Let’s bring that down a little,” Stiller says. He smiles, flicks his pen on the notebook, and adds: “That little bump was kind of a mistake anyway. We don’t need to draw attention to it.”

Re-recording mixer Bob Chefalas freezes the frame, spins a baseball-size trackball on his desk, adjusts a knob and a couple of levers with the swift, assured strokes of a pilot, then replays the moment several more times: Turturro goes back, Turturro goes forward. Turturro goes back, Turturro goes forward.

The screech is way better.

“Good,” Stiller says. He flicks his pen on the pad, scans his notes. “Okay next is, let’s see, 19:08, um”—he tries to read his handwriting—“I have ‘music coming down on the…’ Oh yeah, the score. Right there, there’s like a weird—”

It sometimes goes on like this for hours.

Severance tells the story a group of people who work for a sprawling, shadowy corporation called Lumon—it’s never exactly clear what it does. There’s a division of the company that performs top-secret work, and its employees are voluntarily “severed”: A chip is implanted in their brains that, while they’re at work, blocks all memory or awareness of their lives outside of work, and when they leave the building, blocks all memory of being at work or what they do there.

The show is fantastic, a mind-bending triumph of storytelling that is terrifying, funny, and completely absorbing. From Stiller’s striking opening shot—a young woman wearing a blouse, an A-line skirt, and high heels lies unconscious on a conference-room table while a disembodied voice repeats the question “Who are you?” through a fuzzy speaker—we are in a world that is both familiar (it’s a conference room) and yet…off.

“People do ask me, ‘Why were you drawn to this? You’re not a guy who does these kinds of things,’” Stiller says. He is sitting in his office now, upstairs from the editing room: desk, sofa, two comfy chairs, books arranged on the coffee table at 90-degree angles, a full-length mirror. On a shelf is a DVD set of Escape at Dannemora, the seven-episode show he directed in 2018, the true story of a prison break with a twisted love triangle at its center. “I get asked that about Severance, I heard it a lot about Dannemora. ‘You’re funny. Be funny.’ I get it. But I don’t analyze it. In my mind it made total sense. Maybe it’s something ingrained in me from the movies I watched as a kid that had a big effect on me, and there was a wide range. There were the crazy disaster movies, like The Poseidon Adventure. Or Jaws. Or sci-fi movies in a weird dystopia, like Planet of the Apes. All of those I loved. There was a human quality about all of them, but in a disconnected world. There are human desires and human emotions that are there no matter what, and people figure out a way to fight through barriers. People figure out a way to connect.”

A few years ago, Stiller made a Spotify playlist called SEVERANCE, a seven-and-a-half-hour compilation of songs that kept him in the mood of the new project during the long, long process of making it. (He first got the script in 2016.)

The playlist, like the show, is a mindfuck. On shuffle: “Paradise Circus” by Massive Attack…“Times of Your Life” by Paul Anka…“Water from a Vine Leaf” by William Orbit…“Past, Present and Future” by the Shangri-Las…“Lovely Head” by Goldfrapp…"Daydream in Blue" by Monster...“Glory Box” by Portishead…“Arctic Lake” by Lars Meyer...“Hollowed Heart” by Make Them Suffer...“Work Song” by Nina Simone. Listen to those ten, see where you are. They pair nicely with one of the essential questions of the show: Are we happy people doing good work and joking around the watercooler, or are we the unwitting puppets of insidious overlords who control the world in ways we can’t fathom?

Making a seven-and-a-half--hour playlist to keep you in the headspace of your show is not only a smart, cool idea—Stiller already has a playlist for Bag Man, a script based on Rachel Maddow’s podcast about Spiro Agnew that he wants to direct next—it reveals a tiny bit of the immersive tenacity with which Stiller goes after his projects.

“He’s merciless. He never stops,” says Patricia Arquette, one of the stars of Severance and also of Dannemora. “He never stops rewriting, he never stops thinking. Weekends, holidays—you’d get phone calls late at night, you’d get phone calls early in the morning. Ideas. New things. He has incredibly intense focus on everything—every little set piece, every little wardrobe thing. I’ve never seen anybody so focused on everything.”

Benicio Del Toro, another star of Dannemora, says, “Shooting that was a little bit like playing Twister, jumping back and forth. And that can really make an actor nervous. And Ben kept this cooool, poker-face demeanor, and we followed. He was able to drive that thing home. You know, my daughter’s playing some sports now, and I hear the coach going, ‘You gotta be on your toes!’ And it’s the same thing: You have to be ready for anything that can happen, and make a decision. Some people—and I can throw myself in this bunch—get like a deer in the headlights, and you go ah ah ah!and you don’t make a decision. Ben has no problem making decisions.”

In 1989, after dropping out of UCLA and returning to New York to take classes at the Actors Studio, he had an amazing, potentially career-making breakthrough. He was hired as a writer on Saturday Night Live, with almost nothing on his résumé besides the thing that caught Lorne Michaels’ attention: a six-minute parody of The Color of Money, featuring Stiller as Tom Cruise.

More amazing, after a matter of weeks, he quit. It was unheard of.

“He. Wanted. To be. A filmmaker,” says Bob Odenkirk, who shared an office with Stiller at SNL. Stiller had hoped to specialize in making the comedic short films that the show occasionally aired, but the show wasn’t doing much of that at the time. “He could see: There was no room for us to make films,” Odenkirk says. “So he moved on quickly. And that’s just Ben. I’m sure he could have stayed there, and I’m sure he could have made a lot of films there after three or four years. But he wasn’t going to wait four years to make films.”

Stiller chased his hunger. He scraped together a show called The Ben Stiller Show on MTV, then landed a better-funded version of it on Fox. He pulled in a friend from the Los Angeles comedy scene, Judd Apatow (they had met standing in line to see Elvis Costello), to be a producer, and rounded up a small cast. “We literally had a five-minute conversation where we said, Who should be in the cast?” Apatow says. “We had just seen Odenkirk and Andy Dick do this one-man show that Bob was putting on. And we loved Janeane Garofalo at the comedy clubs. So we said, Okay, these are the three funniest people we know, we’re done! Ben had strong instincts about the type of people who made him laugh.”

The format was simple: Stiller would talk to the camera introducing short film after short film—slickly produced two- or three-minute videos that parodied current cultural artifacts, like the burgeoning self-help movement and the popularity of COPS (Stiller and Odenkirk were cops in ancient Egypt)—and doing blistering, meticulous impressions of people whom Stiller admired: Bono, Bruce Springsteen recording an answering-machine message, Cruise hawking a musical based on his movie career. They were what Apatow calls “cinematic short films.” “A lot of what SNL is right now is what Ben was doing back in 1992,” he says. “If we were doing a parody of A Few Good Men, Ben would shoot it in the same locations where they shot the movie. By satirizing films, he also learned what it takes to make them.” (Later in the conversation, Apatow mentions a recurring sketch in which Stiller played a loser Hollywood agent and would keep adding jokes that could be inserted later, depending on what worked best: “I learned how to shoot comedy watching Ben do those,” Apatow says.)

“We were getting it spot-on,” Odenkirk says. “Which was pretty cool. Nobody had done it the way Ben did it. We did a Die Hardparody—and we had a crane. We had a fucking crane! How the fuck did we get that? In a little sketch on a little show?”

That was what Stiller was hungry for. He had already acted in a big movie, Empire of the Sun, shot a couple years before his brief stint with SNL. A small part, but he made an impression. There he was, on location in Spain—his first time on location—acting alongside John Malkovich, Joe Pantoliano, and a thirteen-year-old kid named Christian Bale. The director: Steven Spielberg.

“As a kid who watched his movies and they made mewant to make movies, working with him was as exciting as you’d think it would be,” Stiller says. “Growing up, any time he made a movie I would go and watch it, and I would read about it, and I’d watch the making-of—The Jaws Log. I would drink that up.”

On set, Spielberg welcomed Stiller to watch his preparing certain shots and explaining what he was doing. Empire, set largely in a Japanese internment camp during World War II, was filmed before CGI, and there were detailed model P-51 Mustangs, and cutouts lined up to make it look like there were lots of them on the runway. Then the actual planes would fly in from an airport in Seville, and the cast would get updates so everything could be timed to the second: twenty minutes out, ten minutes out, five minutes out…

Whatever this feeling was, Stiller wanted more of it.

He’s supposed to meet the Severance visual-effects team on Thursday afternoon to finalize episode nine. But his son recently suffered a knee injury playing Nerf basketball, and the doctor recommended surgery, so now he has an appointment to take his son to a surgeon to explore what exactly the surgery would be. Severance premieres in two weeks, but there is not a question of what he will do today: He will cancel with the VFX team and take his son to the appointment.

In the nineteen years since his and Taylor’s daughter, Ella, was born, in 2002 (their son, Quinlin, was born three years later), Stiller has acted in all three Night at the Museum movies, two out of the three Meet the Parents movies, Anchorman, Dodgeball,three Noah Baumbach films, seasons of Curb Your Enthusiasm and Arrested Development, and a lot more, and also produced, directed, and acted in both the epic comedy Tropic Thunder and the underrated remake The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, and produced and directed Escape at Dannemoraand Severance.

He worked a lot. And lately, he and his daughter have been talking about that.

“She’s pretty articulate about it, and sometimes it’s stuff that I don’t want to hear. It’s hard to hear,” Stiller says. “Because it’s me not being there in the ways that I saw my parents not being there. And I had always thought, Well I won’t do that. But then it’s that thing that, like, I was trying to navigate my own desire to fulfill the hopes and dreams I had, too. And that doesn’t feel great, but it’s important to acknowledge.”

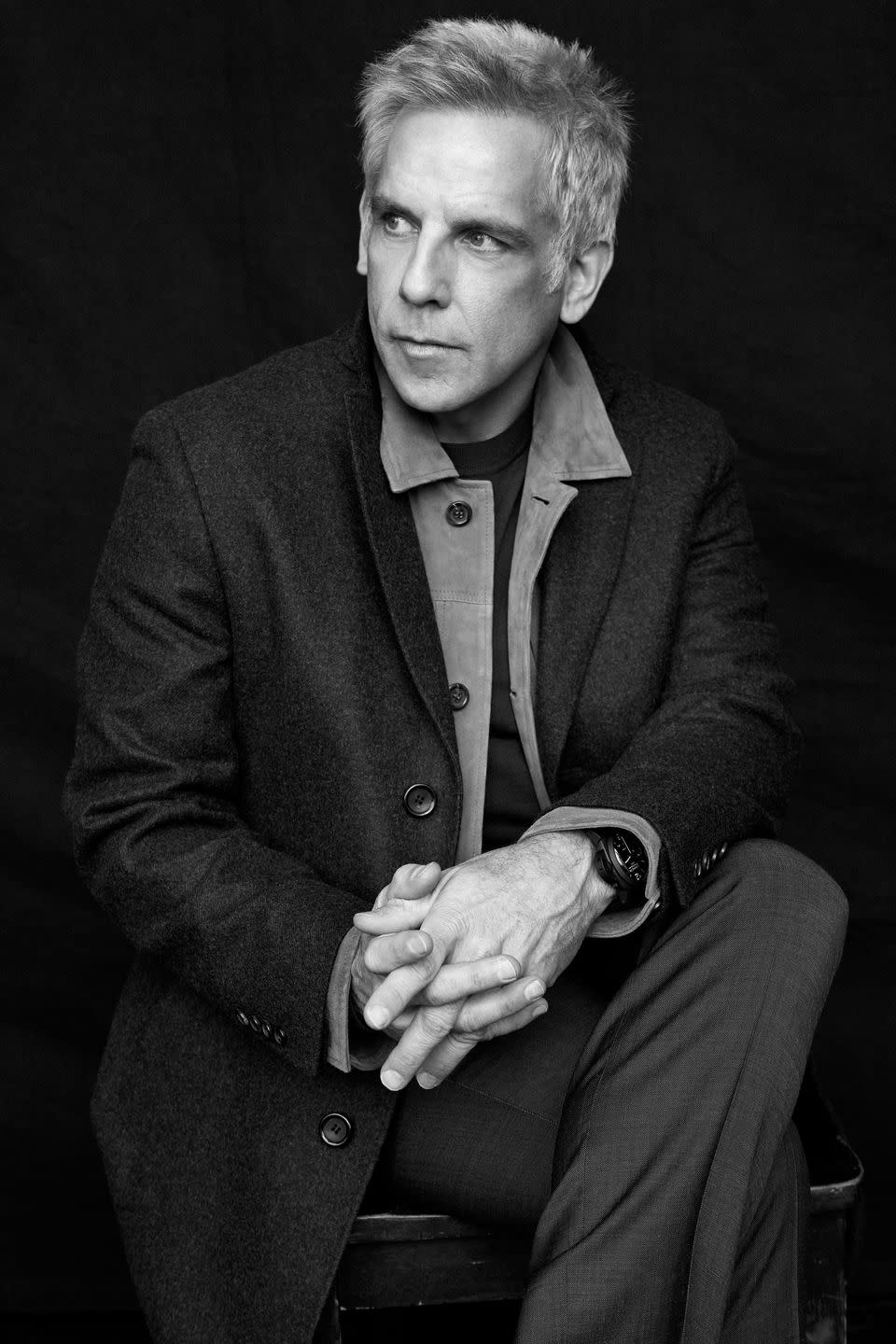

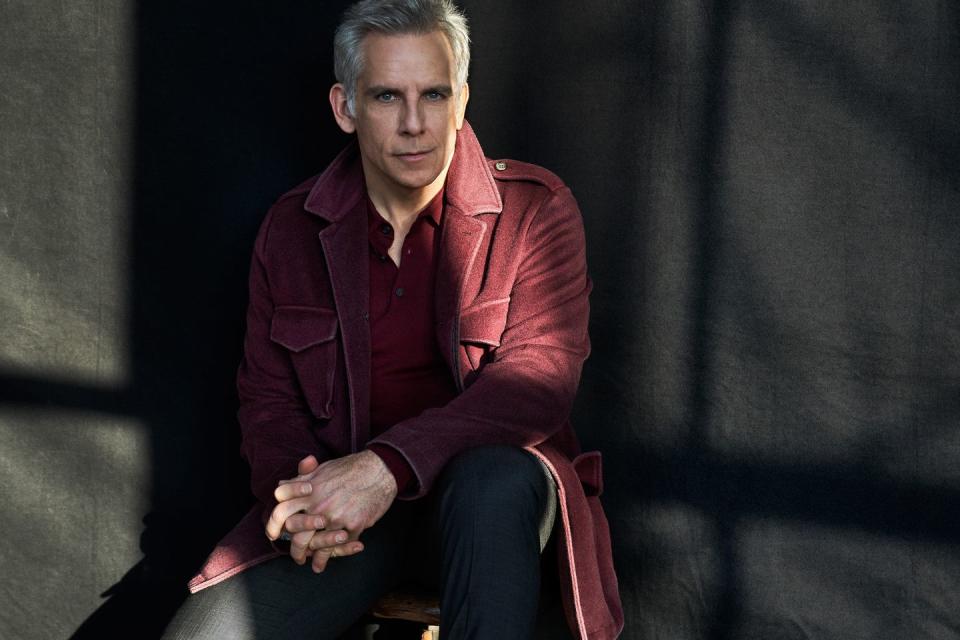

His hair is mostly gray, but he has all of it. His face looks young and unlined. His blue eyes are lively, and when you’re talking, he looks into yours. He looks as trim and fit as he did when he was galivanting half-naked with Téa Leoni and Arquette in Flirting with Disaster twenty-six years ago.

The one big difference between Stiller then and Stiller now is that today’s version canceled the VFX session to take his son to the doctor.

“What I’ve learned is that your kids are not keeping score on your career,” he says. “It would be solipsistic to think that my kids actually care about that. They just want a parent who’s emotionally present and supportive of them. That’s probably what they want more than”—a deep, loud laugh—“for me to be going off and pushing the bounds of my creativity.”

Back when he left SNL to create The Ben Stiller Show, that push was all that mattered, and it seemed to define him for a long, long time: He chased silliness, he chased seriousness, he chased comedy, he chased directing. He worked with De Niro, Streisand, Hoffman, Cruise, Hackman, Spielberg, Baumbach, Wes Anderson, Apatow, the Farrellys, Aniston, Eddie Murphy, Owen Wilson, Larry David, Garry Shandling.

Odenkirk, who sweated and bled with Stiller writing and acting in the show that propelled both their careers forward, says, “Sometimes his personal drive, and probably the pressure that he brought to his own existence—and my hope is that’s loosening up as he gets older; I have to believe it is—I think that could sometimes make him distant or remote, because he’s just got a lot of thoughts going on in his head. Especially when he was young, my sense was he was feeling a lot of pressure that he put on himself to get somewhere.”

Still, there is something that hasn’t changed: what Dannemora star Paul Dano calls Stiller’s “tenacity for the details, which is maybe the number-one thing I could ask for in a director.” Because what is a two-hour movie, or a nine-hour show, but a collection of details that add up to a story? Adam Scott, who plays the protagonist in Severance, says it’s what he admires most about Stiller. Scott was twenty-one when Reality Bites came out in 1994, and the details of that film astonished him even then. “It felt like a mirror to the way we were dressing, the things we were talking about, the cigarettes we smoked, the apartments we lived in—it was exactly where we all were, or a lot of us anyway,” Scott says. “Ben was getting all of the details right, before anyone else knew they were the details.”

Stiller used to have a ritual at the beginning of every movie he directed. He would gather the cast and crew, say some inspiring words of encouragement, and then, in the Jewish wedding tradition, break a wineglass by stepping on it.

On Zoolander 2, after wishing everyone good luck, he stepped on the glass and a shard pierced the sole of his shoe and sliced his heel. “Which was probably a harbinger of things to come for that movie,” he says. The movie reportedly cost $50 million to make, featured an A-list cast and cameos from the highest levels of the fashion world, and made only $29 million in the U.S. and $57 million worldwide. The glass thing? He hasn’t done it since. It was like a warning.

It was also, maybe, a great thing.

“If Zoolander 2 had been a huge hit, and then people were saying ‘Zoolander 3!’ ‘Do this movie! That movie!’—that might have taken me off the road of having the space to work on developing Dannemora,” he says. “I might have gotten distracted by other bright shiny objects, but instead it opened a path where I could just do what I’d honestly wanted to do for years and years, which was: just direct something! To say, I’m just going to work on this project that I want to work on, because it takes a little time to get these things going, and if you don’t stick with it you don’t get there.”

Get Esquire magazine in the mail! Subscribe here.

That question he gets—You’re funny. Why are you doing serious things?—doesn’t apply. “Sometimes people say the hardest thing to do for an actor is comedy, and if you can do comedy you can do anything,” says Del Toro. “I think it might be true, and it might be true in directing as well. A lot of people say to me, Ben’s Escape at Dannemora, he’s completely out of his element, and he did so well. And I kinda go, When you’re good, you’re good.”

By the way, Stiller says, he’s as proud of making people laugh as he is of Severance. “I wouldn’t want anyone to think that I want people to not like Dodgeball,” he says. “I’m really grateful for Dodgeball. When I think about it, I laugh. I like the movie and the ridiculousness of it, and there’s part of me that would want to keep doing that stuff. It’s just trying to figure out, What’s going to engage me in this moment? And some days it does feel like a silly comedy could do that.”

He wants to act again. It’s been five or six years, and he never thought he would be away from it for that long. He’s been talking a lot lately with Helen Childress, who wrote Reality Bites, and they’re inching toward working together again on a movie she would write and he would direct and possibly act in. “It’s like a cousin of Reality Bites. Like a distant sequel, even though it’s not,” he says, and leaves it at that.

When the pandemic began, he and Taylor—who were still living apart—decided that it would be best for Stiller to move back into the family home, which would be the only way he could see the kids during those early months of lockdowns. “Then, over the course of time, it evolved,” he says. “We were separated and got back together and we’re happy about that. It’s been really wonderful for all of us. Unexpected, and one of the things that came out of the pandemic.”

He draws a quirky, funny, Stillerian analogy about the kind of realization that makes a marriage work: “A few years ago, I realized I don’t like horseback riding. If there’s an opportunity to go horseback riding, I’m probably not going to do it. Now, I like horses! I think they’re beautiful. I like petting them. I like watching people ride horses, I like watching my kids ride horses. I just don’t really love riding horses. And once you know that, it just saves a lot of energy. So, yeah, I think we have a respect for the ways that we’re similar and the ways we’re different. And I think accepting that, you can really appreciate someone more because you’re not trying to get them to change for you. Once you accept that, you save a lot of energy. ‘This is something that works for me; this is something that doesn’t work for me.’ If you have that trust level with your partner, you know that me saying ‘I don’t like doing that thing’ is not me saying ‘I don’t like you.’”

He’s sitting in an apartment he and Taylor keep in Manhattan, drinking a Snapple. On the coffee table, books are displayed at perfect right angles, as they are in his office, but otherwise the apartment is cozy, lived-in. Lots of refrigerator magnets.

He talks a little about his parents’ old apartment farther uptown, which now no longer belongs to the family. “There’s that thing about the finality of death—the finality of things in life. ‘Now it’s not yours anymore. You can’t go there.’ You don’t have access to something you’re used to always being able to go to. I think over the last couple years I was trying to figure out how to hang on to the feeling of that place, knowing that I wouldn’t be able to go there.”

He pauses for a moment.

“I was lucky to have my parents live as long as they did, but of course when you lose your parents, you still miss them. And it’s almost the longer that they’re there, the more it seems they’re never going to go away.”

Another moment.

“You know?”

The other day, when he pulled out his phone and pressed Record, he walked through the whole place, filming the empty floors, empty walls. Slowly, and without narrating. Down the hall past the Big Living Room, past his old room, Amy’s old room, the room where his parents kept their files. In the corner living area where there was always a couch—his mom would sit and do her New York Times crossword or read, or sit at her typewriter.

The recording lasts a minute or two. Maybe he’ll use it in the documentary.

When he and his sister were cleaning the place out, they found their father’s shooting script for The Taking of Pelham One Two Three. The movie was filmed in New York in 1973, and once Jerry brought Ben to the set. During the filming of a scene in which Jerry and Walter Matthau drive a police cruiser through a toll booth on the Triborough Bridge, the director let the boy ride in the backseat. In the shot that ended up in the movie, we see the two cops in the front seat, but we don’t see little Ben Stiller hiding in back, smiling ear to ear.

After shooting the phone video that Sunday, he took a deep breath, then left the apartment for the last time. He rode the elevator down to the street. The doorman smiled and said, “End of an era.”

Stiller recaps his Snapple. Today he’s talking about the future, and about making shows and movies that he’d want to see. Like Bag Man. Like Severance. But first there’s something else he has to do.

He checks his watch, puts on his coat and hat. He walks out of the apartment, rides the elevator down to the lobby. The doorman hands him the key to his car, which is waiting for him out front with the hazards flashing. He thanks the man and ducks out into the rain, climbs into the driver’s seat, and hurries to pick up his son. They’ve got to figure out what’s going on with that knee.

Photographs By Mark Seliger

Styled by Chloe Hartstein

Grooming By Jennifer Brent using CHANEL Beauty

Ryan D'Agostino is Editorial Director, Projects at Hearst, and previously served as Editor-in-Chief at Popular Mechanics and Articles Editor at Esquire.

You Might Also Like