Barbara Stanwyck, an obscene typo and the sordid story behind Double Indemnity

Surprisingly, the idea for Double Indemnity – Billy Wilder’s film noir masterpiece about a gold-digging femme fatale and the spineless insurance agent who falls under her spell – was prompted by a catastrophic printing mistake at a smalltown rag during the Roaring Twenties. Reading through the freshly printed first edition, one of the editors was shocked to see an ad for women’s underwear which should have read: “If these sizes are too big, take a tuck in them.”

He ordered the “f” to be changed to “t” for the next edition and eventually extracted a confession from the printer about how the mistake had made it into the paper: “You do nothing your whole life but watch for something like that happening, so as to head it off, and then, you catch yourself watching for chances to do it.”

James M Cain, then a young reporter, heard about this louche blunder, and became intrigued by the idea of a man longing to commit the one crime he is responsible for preventing, using his specialist knowledge against his employers. For years, the idea remained filed away in his subconscious until another real-life story came along and gave him the perfect opportunity to use it…

This was the Snyder-Judd murder case which gripped America in the late 1920s. Ruth Snyder had persuaded her husband, Albert, to take out a life insurance policy, with extra cover for a violent death. She and her lover, Henry Judd, had then murdered Albert in a particularly brutal manner. Snyder claimed that her husband had been killed during a burglary.

Police suspected her from the off, and it didn’t take long for them to find the allegedly stolen items hidden in the house. Snyder even gave herself away during questioning. The subsequent trial was big news, and attracted an A-list of celebrities to the courthouse. Damon Runyon, the journalist and soon-to-be-legendary short story writer, memorably described the original real-life femme fatale as “a chilly-looking blonde with frosty eyes and one of those marble, you-bet-you-will chins …”

The guilty pair – who had turned on each other in court – were sentenced to death, and, in January 1928, were “fried” in the electric chair, 29 minutes apart. A photo, taken by a young newspaperman using a camera taped to his leg, of Snyder strapped to “Old Sparky” was front page news four hours after her death.

Following the huge success of his 1934 book The Postman Always Rings Twice, which concerned a woman who seduces a young drifter and convinces him to bump off her older husband, Cain penned Double Indemnity, a similarly sordid tale which took the Snyder-Judd story and wove into it the inside job angle which had been gestating in his mind since he heard the anecdote about the printer.

As the son of an insurance agent (and a former agent himself, briefly), he already had an insider’s view of how the business worked – and how it could be played. He wrote it as a magazine serial, hoping that the serial would then be sold to a movie studio. Although he told his publisher, Alfred Knopf, that it was “a piece of tripe,” he was dismayed when it was rejected by several major magazines.

The story was then sent to five studios. They all came back with the same answer: they would take it, if the Hays Office, whose seal of approval was required for a movie to be released, would clear it. The Postman Always Rings Twice had been knocked back, and Double Indemnity, initially, met the same fate. The Hays report on it read: “Under no circumstances, in no way, shape or form …”

It finally ran as an eight-part serial in Liberty magazine in 1936. Seven years later, Cain persuaded Knopf to publish a trio of his stories, including Double Indemnity, under the title Three Of a Kind.

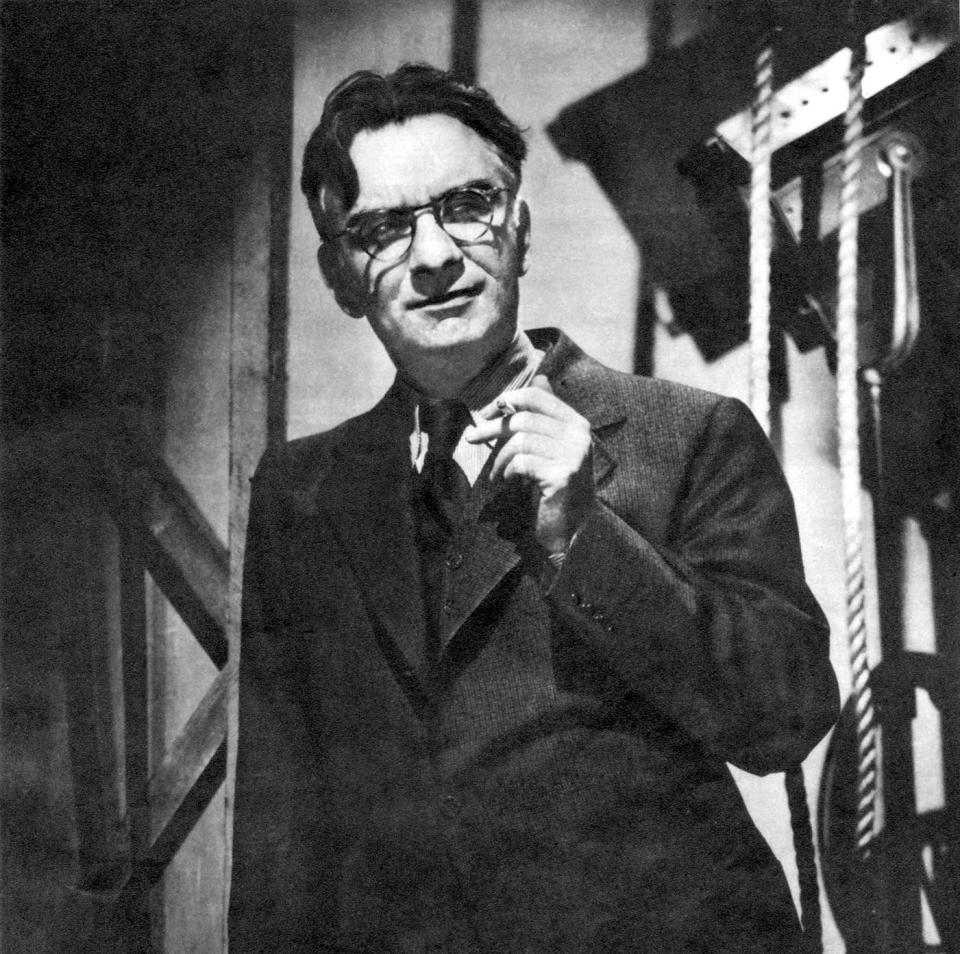

Cue Billy Wilder, the balding, bespectacled 30-something Austrian emigré who, in just five years in the States, had established himself as a writer with a knack for witty banter seasoned with authentic slang. Having co-written scripts for such great comedy directors as Howard Hawks, he had recently followed in the footsteps of his pioneering Paramount Studios colleague Preston Sturges and become a writer-director.

According to Wilder, he stumbled across the source material for his best film to date when, one day, he was unable to find his secretary until someone said: “She’s still in the ladies’ room, reading that story.” That story was Double Indemnity. Wilder claimed that he resolved there and then that this would be his third picture as writer-director, and that he would get around the Hays Office which, fortunately for him, was, during the Second World War, a little less puritanical about the suggestion of sex and more concerned with depictions of violence.

Paramount acquired the rights, but Wilder’s regular partner, Charles Brackett, refused to be associated with such a tawdry tale. Cain was under contract to another studio, so Wilder’s producer suggested another writer of hard-boiled crime fiction – Raymond Chandler. (His novel, The Big Sleep, would become another classic of the film noir genre.) Thus was born the partnership from hell. The strapline for the eventual film’s advertising – “From the moment they met, it was murder” – could just as easily have applied to the writing team: the baseball cap and sweatshirt-wearing Wilder and the be-tweeded, pipe-smoking Hollywood newcomer Chandler.

From the outset, they were at odds. Wilder threw Chandler’s first attempt at a script back at him, and insisted that the two of them write the film together in the same way as he had co-written his previous films – locked in a room for as long as it took.

Chandler described the collaboration as “an agonising experience which has probably shortened my life”. Cooped up for months in Wilder’s fourth-floor office at Paramount, they bickered about everything and continually rubbed each other up the wrong way.

Wilder, who was in the habit of pacing up and down, waving a malacca cane, would take refuge from his partner in the bathroom; Chandler in the bottle of bourbon in his briefcase. At one point, Chandler walked out, having been ordered to open the window once too often. He eventually returned, but only after Paramount had taken onboard his list of grievances (Wilder quoted one of them as: “I can’t work with a man who wears a hat in the office. I feel he is about to leave momentarily”) and drawn up an agreement for them both to sign.

Early on, they argued about the quality of Cain’s novella; Wilder wanted the script to be as faithful to it as possible, while Chandler was insistent that the original dialogue wouldn’t work on screen – “colourless and tame” was how he described it, even in the presence of Cain, who was brought in for a conference at one point.

In the end, the dialogue – which bristled with sexual friction – was mostly written by Chandler. It included such gems as the initial flirtation between Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck) and Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray):

“There’s a speed limit in this state, Mr Neff – 45 miles an hour.”

“How fast was I going, officer?”

“I’d say around 90.”

The problems didn’t end with the writing process. The casting of the leading parts wasn’t plain sailing either. Nobody wanted to play the weak-willed insurance agent Walter Neff. Paramount’s top male star Alan Ladd wouldn’t touch it. George Raft turned it down. “That’s when we knew we had a good picture,” Wilder would later quip. He badgered MacMurray, whose screen persona was amiable all-American, until the actor finally agreed to the part.

Brunette Barbara Stanwyck was the highest paid actress in Hollywood (and the best paid woman in the US) and was reluctant to play an out-and-out villainess (who wears a tacky anklet and a cheap-looking blonde wig previously worn by Marlene Dietrich in Manpower) until Wilder goaded her, saying: “Are you a mouse or an actress?” She earned an Oscar nomination (one of seven notched up by the film) for her knock-out performance. Edward G Robinson, for whom the film represented a shift into supporting roles, stole scenes as Neff’s boss, Barton Keys, whose ulcer unfailingly alerts him to fraudulent insurance claims. Even Alfred Hitchcock was impressed.

The film – with an ending dreamt up by Wilder, after he had already filmed one with a gas chamber – emerged as a distinct entity to the novella. And James M Cain was among those who were blown away by it. After numerous viewings, he concluded: “It’s the only picture I ever saw made from my books that had things in it I wish I had thought of.”

From the Moment They Met it was Murder: Double Indemnity and the Rise of Film Noir is out May 2