Alex Winter Knows the Perils of Child Stardom First Hand. That’s Why He Made 'Showbiz Kids.'

Silent film star Diana Serra Cary performed her own stunts—she was thrown from a moving vehicle, held underwater, and fought her way out of a set building that had been soaked in kerosene and lit on fire. She was four years old.

Known as "Baby Peggy," Cary made millions before she was old enough to attend kindergarten. She was one of the last living links to the silent film era, but she could also testify to the experiences of early child stars, who worked in an era that found the management of their safety and their earnings laxly regulated.

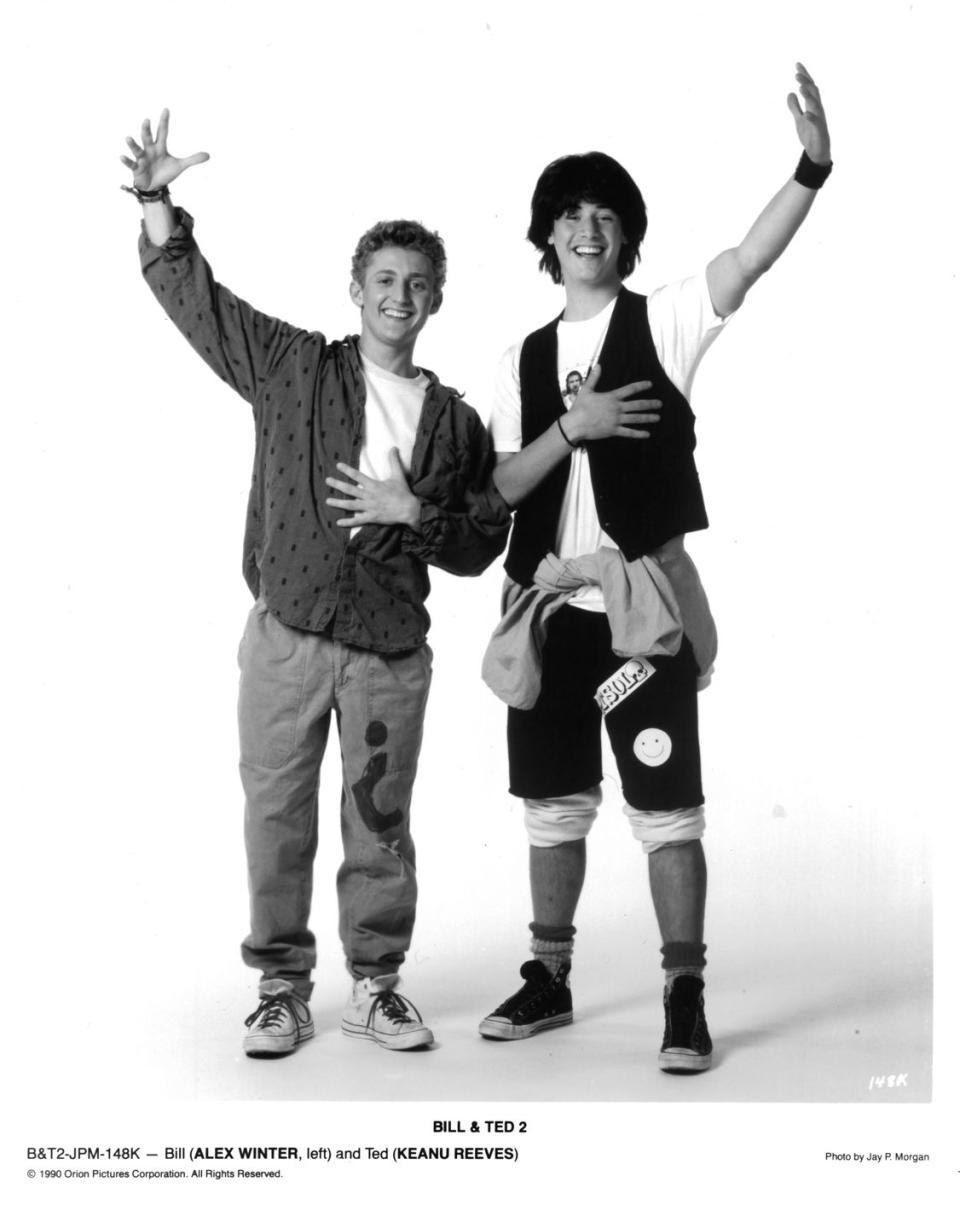

She died earlier this year at 101 years old, but before her death, Cary was one of many actors interviewed in HBO’s new documentary Showbiz Kids, which examines the lives of child performers and is directed by documentarian and actor Alex Winter. Winter is most recognizable for his role as Bill in the Bill & Ted film series, but before he appeared in the now-classic comedy, Winter was a child actor. In 2018, he revealed that he was sexually abused by an adult during his years as a child star, and Showbiz Kids grapples with the sexual and non-sexual abuse that children have been too-often subjected to in the industry, as well as the familial pressures, isolation, and the joy of acting that young performers can experience.

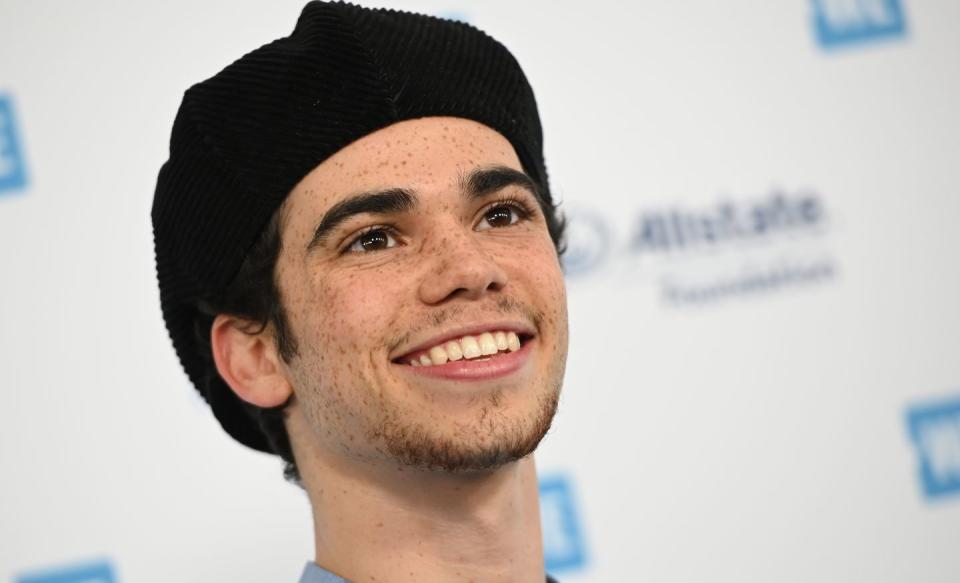

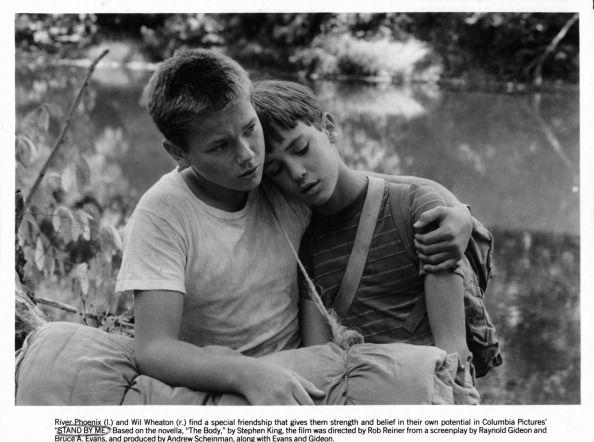

Showbiz Kids features intimate interviews with stars including Evan Rachel Wood, Milla Jovovich, Jada Pinkett Smith, Mara Wilson, Wil Wheaton, Todd Bridges, ET’s Henry Thomas, and the late Cameron Boyce, who died last year of epilepsy at the age of just 20. Esquire talked to Winter about making the film, what it’s like to be a child actor, and his work on the upcoming Bill & Ted Face the Music, which is scheduled to be released in August.

The interviews in the film are just so intimate. Could only an actor have made this documentary?

I do know that a big part of the reason why I wanted to [make the film] was I didn't feel that I had ever seen the story told from our perspective. Mara Wilson has communicated to me that she wouldn't have done it if it wasn't being made by someone who had actually lived through it. So, I guess the answer is yes.

The interviews with Diana Serra Cary before she passed away are so incredible, and I was wondering if you could speak a bit about what the working environment was like for early child movie stars like her.

It was, in a lot of ways, much harsher than it currently is, and in just as many ways it's identical. Some of the differences are just legal. We have the Coogan Law today, which protects the finances of children. You have emancipation possibilities today that you didn't have back then. You have the amount of hours that a child can work, and the requirements for tutors, and on set supervision that you didn't have back then. So, those are the differences.

The similarities are striking. The first person experience is pretty much the same: Diana went through the same ups and downs that all of the kids went through, all the way to Cameron, who's super young. The thing that struck me when I interviewed Diana that was surprisingly cathartic was how much I identified with her story. As she was talking, I just thought, “My God, this is literally my journey coming out of this 101-year-old woman's mouth.”

There was one great moment where Evan Rachel Wood says that you can tell a child star by the lonely hobbies they developed. Do you have any skills that you developed from this time? Are there any other ways that child actors can identify their tribe?

I was absolutely Evan as a kid. I was alone most of the time. And I was in two long-running Broadway shows back to back, which means I was either on stage, backstage or on my way to and from the theater. And I remember when I was doing King and I, when I was 13... This was the '70s, right? There was those little plastic video battery-operated football games, it was really crude, it was literally a dot just moving its way across what supposed to represent a football field. And I think I wore a hole in that machine; I would just sit backstage and play it for hours. And that was my weird idiosyncratic singular hobby that I had.

But you can tell your tribe by many things. There are things we go through in this experience that are very, very similar regardless of age, race, gender. And you feel a real kinship for other people who are doing or have done this kind of work.

I think everyone's mind immediately goes to the negative. Sure, that's included, absolutely. Certain kinds of PTSD or certain aspects of family dynamics that blew up or whatever. But there's also a lot of positives. There's the affinity for performance and dedication to a craft from a very young age and the just sheer unadulterated joy that comes from practicing that craft if that's what you want to do.

Cameron Boyce felt like the ambassador for that joy in the film, which is so heartbreaking to see now. Were you still working on the film when he passed away?

I was knee deep in the film when he passed away. I was just absolutely devastated. It just felt like a cruel joke.

What it underscored for me, though, was something I had always felt, and which the film was working to convey. There are kids who are just meant to perform, and I don't mean that in terms of his destiny. I mean that he loved performing, he was not being shoved on stage by his parents. This was in his blood, and he worked really hard at it, he loved it, and he was great at it. And he had an amazing life. I remember thinking when he passed away, “Thank God that he got to do what he did, because he really had a great life, as brief as it was.”

He would have been a great adult actor, right? No doubt in my mind about that. And frankly regardless of his career, he was just a really interesting human being, and he would have had an interesting life whatever he was doing. So, yes, I was utterly devastated. But I'm really grateful that we got to meet and spend some time together.

You came forward as a survivor of abuse as a child actor. Could you talk a bit about what made you decide to take the really big step of going public?

I'm turning 55 in a few days; I've been around a little while. I've been dealing with the issues as a result of my abuse history my whole life. I had extreme PTSD, I had to do a lot of therapy for that. And I've been working with abuse and assault organizations for decades, youth organizations of different stripes, not all related to abuse. And so I had done a lot of work, I'd been through it already.

What made me actually take it public was a sense of responsibility when the Me Too movement happened. It was so beautiful and utterly surprising to watch that fuse light and just keep going, with Tarana Burke and African American girls, and then it spread to women in general and then it spread to men and then it spread to boys, and you started seeing some boys in the entertainment industry, now men, speaking up. I thought, “My God, it's going to keep going. This is it, this is that big watershed moment that most of us never thought we would ever see in our lifetime, when you would be able to speak about these things publicly in a nuanced way,” which you just could not do at all before Me Too. It's that cut and dry. Nobody understood it, it was very taboo, it was a no go zone. It wasn't a safe thing to discuss.

So, while I was good, I had done my work, I felt a responsibility to add my voice to the expanding chorus. Just holding up my hand and saying, "Yeah, me too."

The movement has reshaped Hollywood in so many ways, but are there any changes that you think are making the industry specifically a safer place for kids?

Oh, for sure. I worked in production, right? I've directed a lot of kids' entertainment commercials, half-hour comedies for Nick and Disney, you name it. And those rules are really strict, and they're getting stricter all the time, as well they should. There are many more rules and laws in place that help protect the kid.

Coming up, I generally found that most people wanted the best for me. I didn't look around the environment and go, "Oh my God, I'm around a bunch of predators and nobody cares if I live or die." That was not my atmosphere.

The problem was, it was very difficult to communicate the problems that you were facing. So, that's the thing that's changing incrementally, but significantly—if I were 13 years old and experiencing what I was experiencing now, it would be far easier for me to go to a stage manager or an assistant director and say, "You know what? I'm in serious trouble and I don't know what to do." There was no line of communication to do that before.

I don't think that that is a cure all, because many people, parents, kids, whomever, will still be too frightened to speak up for whatever reason. However, there are many that will speak up because they know that this landscape has changed.

Why do you think the idea of child stars and child stardom has such a hold on our imaginations?

I think it's because our own childhood is such an incredibly marked period in our lives, and we remember the details. The peak experiences of our childhood have such a foothold in our memory. It is our development, our entry into the world. It also is ripe with possibility. It is this whole fascination that the culture has with youth, and just having your whole life in front of you, and being this innocent entity that is embracing all the aspects of the world for the first time with so much life still in front of them.

I think at the end of the day, when we look at a child in a film, that has emotional resonance for us, and that child has double resonance for us because of our own memories of our own childhood. We watch that innocence.

Another really moving moment for the film was when Evan talks about deciding to keep her child's life from the public after her own experiences. Are there any ways that you feel like being a child performer has informed your parenting?

Of course. I have a very wide-eyed view of childhood, where I think that the child should have the ability to flourish and actualize as they are, develop organically. And that wouldn't preclude a life in the entertainment industry if that was really what that meant to that child. I have three boys and they're in the arts, my eldest is in college, in art school as a painter, my stepson is a jazz trumpet player and my little one is a 10-year-old who just does what 10-year-olds do. None of them are me, none of them are Cameron Boyce, or Mara Wilson or Evan. None of them are like, "I have to perform."

When I was five, I was telling my parents, "I have to be on stage, I have to perform," and they obliged. I work in the industry, my wife works in the industry. I wouldn't just put my child into the industry because I can. So, it impacts my parenting in the sense that I'm very aware of the dangers that are out there, but I'm not a hyper paranoid or restrictive parent. I think that children should have an expanse in which to live and play provided that that's safe. It's my job to make sure that's safe.

The film's score by Tweedy was amazing. How did that come about?

I'm still pinching myself that I got them to do it, and that they just dove in seriously and did such an amazing job with it. I am a huge Tweedy fan going back to the Uncle Tupelo days, and was a huge fan of the early forays of Jeff and Spencer's band, Tweedy.

When Wes Hadwell and I were cutting the movie, the only [temporary score] I was using was Tweedy. There was a gentleness to it that really embodied the way in which I was approaching the story. But there was also depth, and this sense that it's fathers and sons, which is just interesting to me, because so much about what the movie's about thematically is family dynamics.

So, at a certain point, I thought, “Well, hell, what do I have to lose if I ask them if they would actually score it?” And I got them a really early cut, and they really responded to the cut. They had very specific ideas, and they were completely in line with what I wanted to do. And so we started putting tracks together for it. And then I went to Chicago and we all mixed it, and I got to bring my eldest son with me, who's an absolute zombified Wilco fan. It was an absolutely amazing experience.

I watched Bill & Ted last night, and the film just made me so happy all over again. What is it about these movies that just makes them so endearing?

Honestly, I think that Chris Matheson and Ed Solomon wrote characters that are legitimately sincere, that are genuinely good friends, and that have an open and curious attitude towards the world. They're more like nine-year-old kids than they are really like 16- or 17-year-old kids in a lot of ways. But I think there's an infectiousness to the sincerity of their friendship and of their innocence.

Keanu and I always approached the characters the same way, which was to play them straight, really find our own internal joy, sensitivity and innocence. And what friendship means, what that bond means. We took it seriously then, we took it seriously when we played it recently.

Was it harder to tap into that childlike quality all these years later?

It wasn't like falling off a log, it took work. But it took work then too. Neither of us are even vaguely like those people. So, we had to find those guys back then and we had to find them this time.

I was studying friends that I had, other people I knew that were my age but had those qualities, what made them tick. I really didn't want Bill to be a caricature. Certainly Keanu didn't want Ted to be a caricature. We wanted to play them as real people but we had the qualities that made us who we were. So, it was fun. It was a fun thing to play with, but it did take work, yes.

What does it look like for these guys to be grown up?

They love their family. They've always had a real love for life, so they love their wives and their kids and they love playing music and they love hanging out together. It's not really that idiosyncratic when you think about it. It's just you layer on top of that the great language that they have, and that's where the fun starts.

You Might Also Like