When Will I Be Able to Retire This Essay?

Not so long ago, we saw boisterous tributes to essential workers. Americans celebrated legions of the working class along with the “healthcare heroes.” Congress even sponsored a “HEROES Act.” These celebrations paid homage to a people who were once invisible, but whose life-threatening sacrifices brought them out of the shadows. But the uprisings in response to George Floyd's killing by Minneapolis police now expose the hypocrisy of the fleeting ovations. They unmask a vicious backlash against working-class brown and black people.

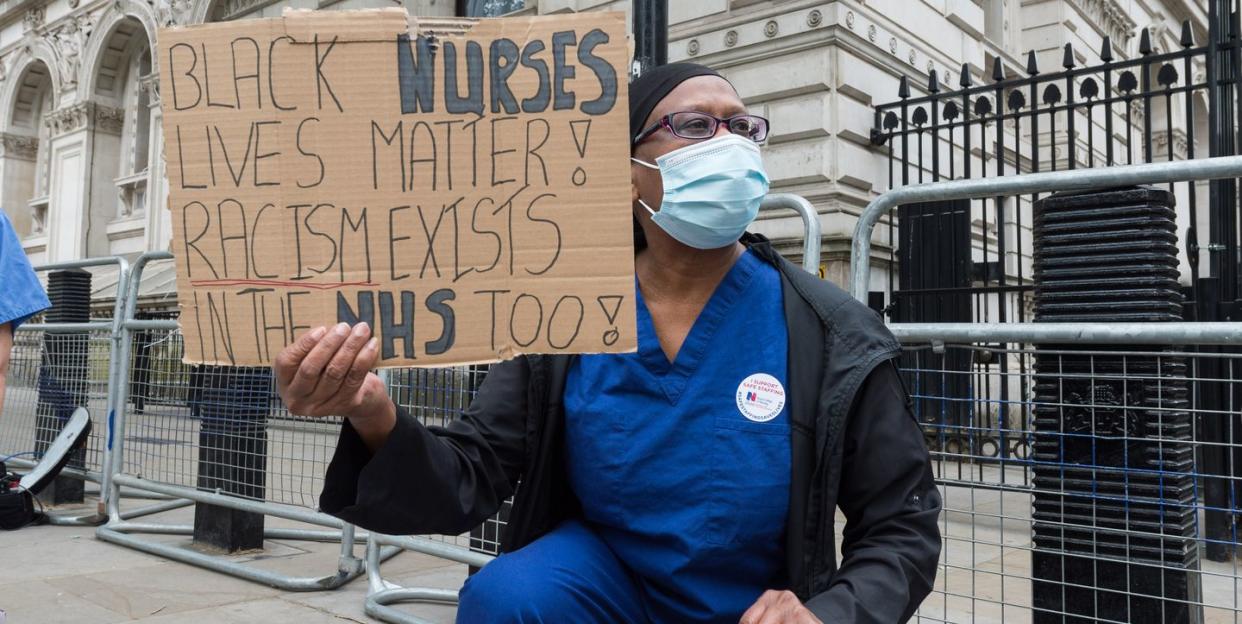

You’d think a country that can equip every cop like a soldier could equip every nurse like a nurse. Police outfitted in paramilitary gear have used disproportionate force even against peaceful demonstrators. These militarized attacks have a further perverse effect: they show us the glaring difference in the preparedness of cops versus frontline medical workers, many of whom are also black and brown, a raw ignition for this political anger. A country that just professed its love for working-class frontline workers will ignore all the festering causes of these demonstrations. The protests do not just come after a police killing, but after a virus ravaged its way unequally across black and brown communities.

From New York to Minneapolis to Los Angeles—and many other cities where the protests flare—COVID-19 deaths did not just disproportionately afflict black and brown communities. So did the response. Members of the Trump administration sometimes implied that irresponsible people who suffered from chronic health conditions, such as hypertension, obesity, and diabetes, were to blame for their fatal complications. But any given individual’s condition plays only a part: these communities’ risk shot up significantly when factoring in density, reliance on public transportation, healthcare access, financial ability to “self-isolate,” and quality of care.

President Trump equivocated, denied, and sat on his hands during the critical first two months of the pandemic, and has now watched the virus kill roughly 23,000 black Americans. He scarcely uttered a breath of sympathy, but did offer abundant bragging about his “ratings.” By taking calls from oil and financial executives during the height of the crisis, as opposed to executing a coordinated national response that included urban communities being eviscerated, he made clear where his administration’s priorities lie.

Adding insult to injury, the federal government's response worsened class and race divides. Twenty large hospital chains received more than $5 billion in federal grants, recent reports show, even though they still sit on more than $100 billion in cash reserves. Meanwhile, many hospitals with demonstrable financial need, and which serve low-income people, have received paltry federal grants that may not be enough to sustain themselves in this crisis. This gap reflects the other reality, that $170 billion in federal tax breaks are spilling overwhelmingly to the country’s richest people and biggest companies.

Employment has dropped sharply in the last two months overall, with black women facing the disproportionately largest job losses of any demographic group. As of April, the latest data available, the unemployment rate for black people in the labor market is 16.7 percent, compared to 14.2 percent for non-Hispanic whites, though neither figure may capture how many people are truly out of work. One in two members of the adult black population is now out of a job, though some are retired, in graduate school, or incarcerated.

The Trump administration and its supporters need to acknowledge publicly that the uprisings are not just in response to George Floyd’s death. They are memorializing legions. The protests burn with righteous anger over the digital video showing the murder of Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, and the horrific shooting of Breonna Taylor in Kentucky. But there's also Dezann Romain, a 36-year-old black woman who became one of the early, devastating COVID-19 casualties in March. Ms. Romain was a public high school principal at the Brooklyn Democracy Academy, who mentored youth and tirelessly nurtured her neighbors on the front lines of her community. That is why she was more exposed to coronavirus in the first place.

Witnessing COVID-19's assault on black people gives me shivering bouts of déjà vu. Back in 2005, I wrote an essay about Hurricane Katrina. “The State is fucking black people over.” That was basically the essay. The government’s response to the disaster opened a billion-dollar spigot in federal contracts, including to the well-connected GOP-leaning giants, such as Halliburton and Bechtel. In 2010, a BP oil rig exploded, unleashing millions of gallons of oil into the waters of the Gulf Coast, polluting the fragile ecosystem and wrecking the lives and livelihoods of its working-class people. Then the financial meltdown. Then COVID-19. And now George Floyd.

I could recycle my Katrina essay for virtually all the subsequent natural, medical, and financial disasters. In each instance, the federal government had ample warning about the risks of an impending catastrophe, but failed to prepare. When the disaster hit, the government’s incompetence commingled with its indifference where people of color are concerned with devastating consequences. Then lobbied corporate interests prevailed in the so-called “recovery” over the needs of black and brown citizens. A toxic brew of negligence, corporate favoritism, racist double standards on attributing blame, and Republican intransigence left the country with unequal outcomes defined by class and race. People had no option but to get out in the street and protest.

When am I going to be able to retire this essay?

You Might Also Like